What Happened to Happen

A life in the day of Craig Mitchelldyer, the Portland Timbers Director of Photography

This photograph is the one.

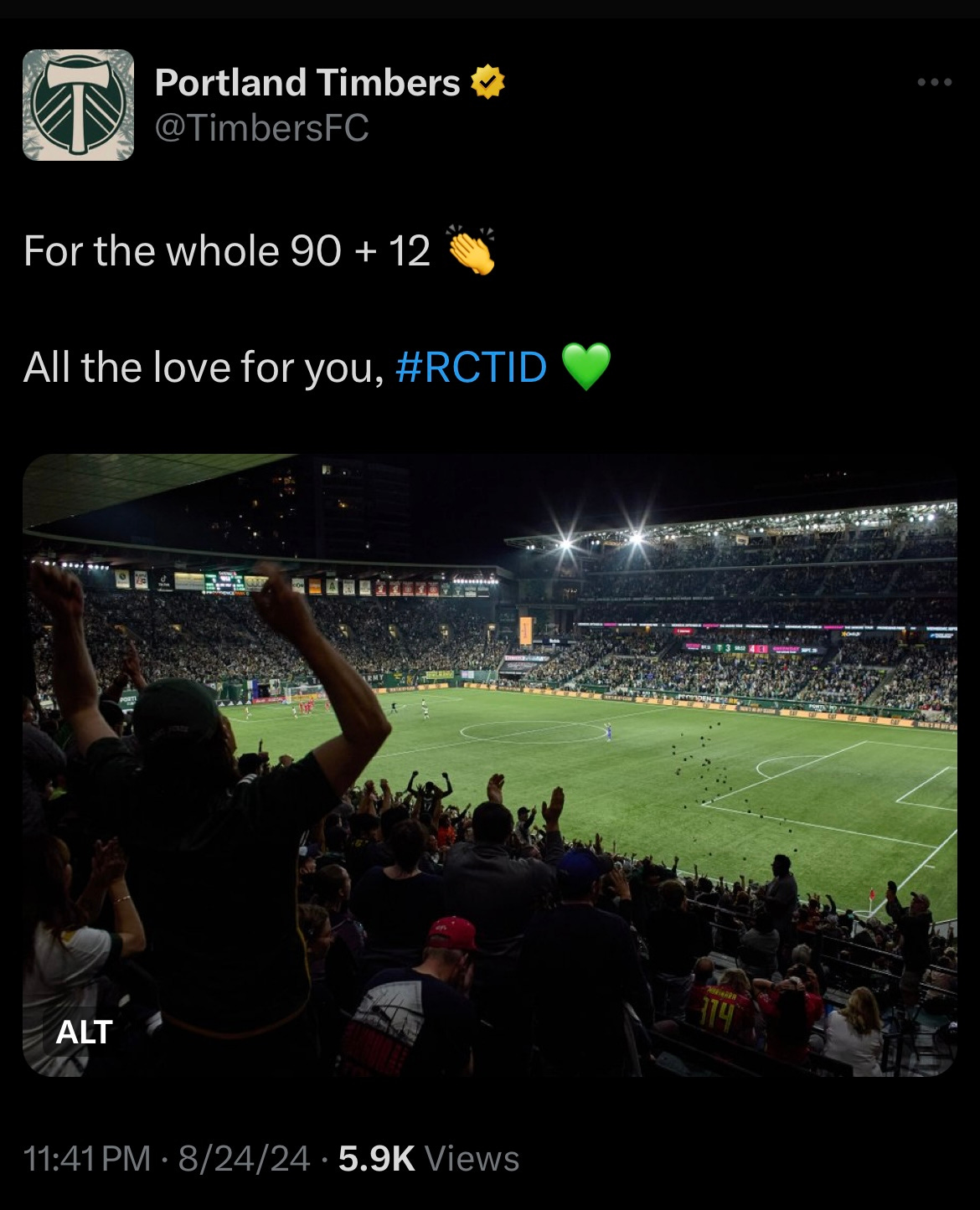

It’s from the 83rd minute of the Timbers’ August 24 match against St. Louis City SC, just after Antony headed home an equalizer that drew the teams level at 4, after the Timbers had thrice been down 2 goals throughout the match. Timbers Army with arms up, the moment Felipe Mora realizes his teammate’s feat, Eryk Williamson bounding through the background to blast the ball back into the net for emphasis, St. Louis in disbelief that they couldn’t close out multiple leads. Then there’s the goalscorer: At-the-time-22-year-old Brazilian Antony, arms spread, tongue out, triumphantly running in the direction of the camera.

It’s the perfect picture of a club that doesn’t quit, of this 2024 Timbers team that never loses, only runs out of time.

I shadowed Portland Timbers Director of Photography Craig Mitchelldyer for this match, wanting to see what it was like to cover the team from behind the lens, what he might do over a night to tell the stories on and off the pitch. What I found was, a day in the life was impossible to grasp, impossible to convey, because any one moment captured in time just that: one moment. Behind it is a lifetime—passion, professional pursuit, love for what he does. That can’t be reduced to an essay; it can’t be fully captured because it never stops. Everything goes into, but is not fully defined by, each image we see on the outside.

After this match, as it was nearing 11 PM, and we were in his office in the lower level of Providence Park, this is the photograph he told me was his best of the night.

With 5 cameras throughout the stadium, each taking roughly 2,000 shots of the goings on that evening, this one of Antony celebrating in the moments after his goal is THE photograph. THE picture of the roughly 10,000 Mitchelldyer took during the match. And for someone who never thinks he takes a perfect picture, who is always driven to be better at what he does, Mitchelldyer’s endorsement of this specific shot is no small thing.

Too bad he couldn’t use it.*

Moments after this photograph, Antony was judged to be offside. The goal was called back.

Not everything goes as planned, and rarely is the path linear. To tell it true is not to be complete as much as it is to be intentional, to let parts make the whole. In the spirit of Mitchelldyer sorting through the nearly 10,000 photos he took to tell the story of that night—and beyond—below are 8 Mitchelldyeresque moments selected, from what happened to happen, to at least start to see where our stories come from.

1: The Scene-Setter

Mitchelldyer had already been at Providence Park a good half hour before my 3:30 arrival. He greeted me while pushing a cart loaded with cameras, clamps, and a tripod.

“One of the things we’ll do every game day, no matter where we’re at,” he told me, “is we’ll shoot some kind of scene-setter.” This time, he wanted to try something different. [After shooting “in the same place 50 times a year,” as he framed it, I can understand wanting to find a fresh way to start the game-day story. Trying new things, however, is just the tip of standard operating procedures around here.]

The Timbers last played a match just over two weeks prior—a 1-3 Leagues’ Cup road loss to that night’s opponent: St. Louis City SC—, so one underlying theme of the evening was to welcome the fans back to Providence Park, back to Timbers soccer.

This is where my night shadowing him really started, in the southwest corner of the stadium, where Mitchelldyer set a remote camera in the middle of Section 222. From there, we returned to the cart and in-arena concourse where he set up the tripod and a Canon R3. I followed as Mitchelldyer took a picture, pushed the cart a yard or two, took another. He used the field’s center circle as the focal point and, with as much cooperation as a nearly 100-year-old stadium can offer in the way of a level concourse, spent the better part of a half hour taking pictures that would become that night’s scene-setter, sent out on the team’s X account.

“I was just trying to do something a little bit different for that one,” he said in our interview for Podcast Episode 41. “I don’t think it worked out as well as I wanted it to. There are some things I’ll do different next time, probably. But, you know, it’s one of those things: Give it a shot, see if it works.”

This love of visual storytelling—and the desire to always do better, be better—isn’t a that-night thing; it started 6 miles and 30 years from that match at Providence Park, when a high-school-freshman Craig Mitchelldyer transferred from Klamath Falls to what was then Southwest Portland’s Wilson High School. “I liked to take pictures of my friends that were athletes at the time,” Mitchelldyer said of his high school days. “I could go in [the darkroom], make prints of them, give them those prints. And it was just a cool spot to go to, you know, the magic of photography back then, where you take a picture, you spend an hour in the dark room and come out with the actual print in your hands.” After his freshman year, Mtichelldyer moved to the other side of the Willamette, transferring to Milwaukie High School, where his love of photography and desire to keep telling stories was stoked by advisor Bill Fletchner. “I really owe a lot of my career to him, just pushing me to always be better and do better things.”

That’s the drive and desire that had us walking the whole Providence Park inner concourse—push-stop-focus-shoot-repeat—from 222 to the Lodge Boxes in the southeast corner of the stadium. So much time was spent doing that, that we didn’t have enough time to set the other remote cameras on the cart because we needed to get to a pre-match meeting with Mitchelldyer’s team, where I found the prep work for all invoked the same ethos: tell the stories that make us who we are; try things old and new.

Mitchelldyer may not have been completely satisfied with the end product, but it definitely did the job:

2: Soylent Green (and Gold) Is People, Part 1

“We talk about storylines, “Mitchelldyer told me of the pre-match Content-Team meetings, “things to look out for, what we know is going to happen, what we think might happen, things to be aware of. It keeps everybody on the same page, so that everybody knows, ‘Hey, this could be the game that Finn Surman makes his debut, the day we get a [MLS] hat trick that we’ve never had. This could be Eric Miller’s potential 200th game. Be aware when he comes on the field.’”

None of those things happened that night. Miller did make his 200th appearance the next week against Seattle, but both the Surman debut and the elusive MLS hat trick storylines will have to wait for a future date. Nonetheless Mitchelldyer et al. were ready regardless. And, above all, the meeting was what one would hope to witness from professional creatives telling the story of a night, of a club, of a half century. Moving through the August 24 content posts from the club, it’s possible to trace the provenance of most visuals to the brainstorming and planning that happened more than an hour before a player entered Providence Park.

After the meeting, it was back to the pitch proper to prepare. Mitchelldyer rolled out and buried the ethernet cable that could send his photos back to the team in an instant, and we walked the field to set up a second remote camera, this one at field level in the northeast corner.

An added benefit of this access was being able to witness how much of a community the Timbers visual-arts professionals are, and this was exemplified in the times I was able to witness the dialog with Mitchelldyer and Portland-based photographer, Fletcher Wold. Wold, who sometimes works with Mitchelldyer, was this night shooting on contract for the visiting side St. Louis, who did not send a team photographer.

In one of the pre-match-prep walks around the field, Mitchelldyer cued Wold in on the ethernet and power access. At another time, the two talked shop. Those were moments I appreciated the larger family of photographers we have in our northwest corner of the country. It’s a community Mitchelldyer has played many roles in over the years.

“I remember back in high school,” Mitchelldyer told me when I interviewed him for Podcast Episode 41, “when I was reading The Oregonian, there was a photographer, Joel Davis, who was on the Blazers beat at the time, and you would see all his really beautiful Blazers pictures in The Oregonian. They were strobe, they were just amazing pictures. I always wanted to be Joel Davis, where I’m working for a big newspaper.” Having been a fan of Mitchelldyer’s work for a while and then following him this evening, I can claim there’s no doubt he has something to crow about, even if he won’t.

“And now, I don’t want to say, like, I’m one of them,” he shared, “but, they’ve taught me a lot. And now what I try to do—like you were shadowing. You know, you said that it was abnormal to have a shadow with me, and it’s really not—people shadow me at games all the time, because a newer, younger photographer might want to be trying to learn or get into the sport. And I try to bring people to games when I can. So they can see how things work and and ask me questions. And, you know, I really want to help the next batch of photographers come through.”

This is a good place for a 43-year-old photographer to be: Ready and willing to try new things on one hand, and insistent on enabling others through his experience and love for the art on the other. “I’m not going to be doing this forever,” he said, “so eventually somebody else will have to do it. It’s important to have mentors, and it’s cool when you have mentors that help you advance your career, and it’s important to bring the next group along and give them opportunities.”

Even with the access I had at Providence Park that night, all of the things I saw that most people don’t, and the different places we went where I got to see how the proverbial content sausage is made, it was interactions like these—enabling others to have the opportunity to participate, to grow, to be better—when I felt the closest to what it means to be part of our Timbers community.

3: Soylent Green (and Gold) Is People, Part 2

When you see a picture Mitchelldyer took, you see what’s in front of his camera, and it usually tells the story of the moment, the story of the club. What you don’t see, obviously, is the person behind the camera. What’s even less immediately identifiable is the theory and experience of the person behind the camera, where years of labor and wanting to bring the team to others comes from a dynamic relationship to the given moment.

“I’m only as good as the people I’m taking pictures of. If something really amazing happens in front of my camera,” Mitchelldyer said, “it’s because something amazing happens, and I’m prepared to photograph that amazing thing. I can’t take good pictures unless cool things happen in front of me.”

I’ll take that a step further. It’s not that something has to happen in front of him, but something has to happen, and he has to happen to be prepared. He is. And though I’ll speak later of the profusion of preparation that goes into the technical aspects of covering the match, it always comes back to the human connections that unify us as a club.

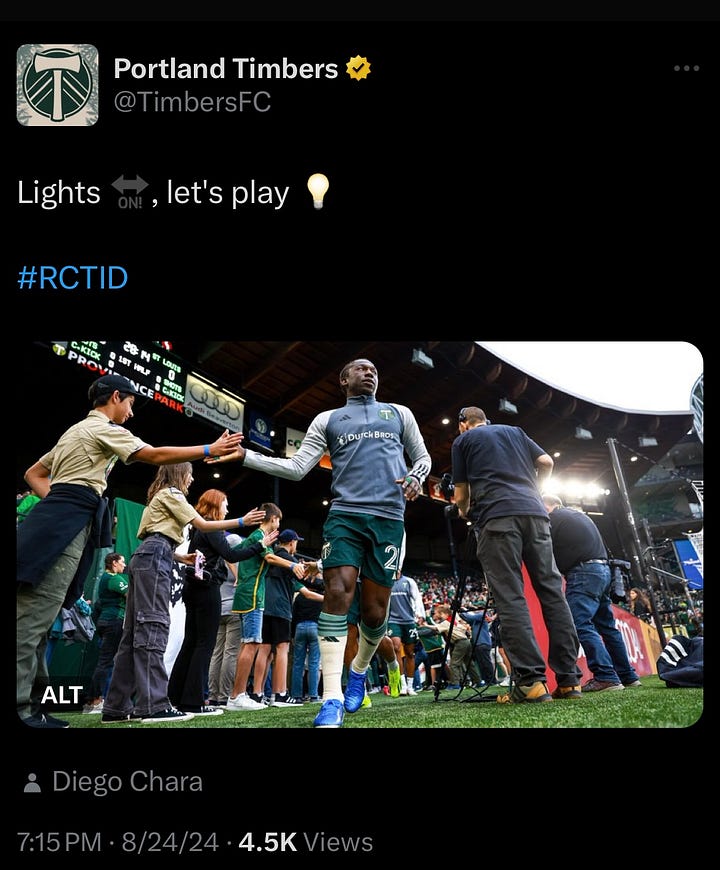

For many fans, this is most embodied through the players, a connection that starts with the Content Team before kickoff. “We want to show that our players have arrived at the stadium,” he said of the player walkups as they enter Providence Park. “It’s game time. The players are here, that kind of thing.” He continued, “a lot of our players have some style, and we want to show off their personalities. That’s one of those things where you see these players on the field, but what are they like off the field? Showing their sense of style and the swagger that they have when they arrive is part of showing the personality of the player.”

But there’s something more to the moment. Something more Portland-Timbers-specific. Like the Lap of Honor at the end of the match, a tradition that dates back to the 1975 Timbers, the arrival of players in an accessible way for fans is something not all teams do and something that’s another cornerstone of telling Our Story. “We want to show the fans that are getting autographs. We want to show that interaction. It’s a very unique thing.” Mitchelldyer pointed out only Minnesota and Toronto do something similar. “So it’s a unique interaction between fans and players. We want to showcase that: Game Day has now officially arrived. The players are in the building. Let’s lock in.”

4: so much depends / upon / a yellow camera / remote

I can’t keep up with all I learned shadowing Mitchelldyer that night. (And, as you’ll see In The End**, I never will; he never stops. I’ve given up on that.) But I have been able to process a few things. How one person can take roughly 10,000 photos in one match, and how those tell a story, is one of them.

In a profession designed to not be seen in order to bring what should be seen to people, where nearly everything is black to reduce unintended reflection and visibility of person and equipment, the yellow PocketWizard remote attached to Mitchelldyer’s main camera stood out to me.

Remember the remotes we set before kickoff? Those are synced with the remote attached to Mitchelldyer’s handheld camera. “As we were passing [the places where we clamped the remotes] I hang those cameras up. And the goal of the remote cameras is to capture the atmosphere and the general view of the stadium, and get some images that will make you feel like you’re part of the crowd when you see them.”

This is how he can be everywhere at once. “If I have three remote cameras, and I move two of them [as we did at halftime, a process that added to what Mitchelldyer’s watch told him was a 30,000-steps-plus day at the office], I can get five different angles,” he said. “The purpose of those remotes is to put myself in multiple places that I couldn’t necessarily get to during the game.”

The four pictures below feature one of these cameras, in two different locations during the game. In the top-left, Mitchelldyer sets up a remote camera pre-match, and you can see the photo taken from it just after the Timbers first goal, to the right. In the bottom-left photo, he moves that camera at halftime, and the photo next to that is from the same camera capturing the crowd reaction to Antony’s would-be-tying goal that was eventually called back, a photo that, if you look closely, is seconds before the photo at the top of this story, with Eryk Williamson about to leap toward goal.

“When I set them to fire at the same time as my other camera,” Mitchelldyer said of the remotes, “it takes a lot of pictures that are throwaways, and then when it pays off is when I shoot a photo of a goal and all the remotes are firing at the same time. And they’re getting the fans standing and cheering at the same time that I’m shooting the actual player with my main camera in my hand.”

Antony’s 83rd-minute equalizer was called back, but Evander’s 99th-minute golazo was not. From Mitchelldyer’s field-level shot, to the Section 222 remote, to the late-night post from the team, the planning, the chances taken, and the success of the remote set-up bring all of us into the moment.

5: [90%] of the Time It Works Every Time

There’s something Mitchelldyer said to me that stands out as an accurate summation of what I saw over the nearly 8 hours we spent together that night: being prepared is the absolute minimum for success, and to do that allows for the last ingredient: “luck,” which he said, “is where preparedness and opportunity meet.” The same can be said about playing the game itself.

Diego Chará has been with the club since 2011. There’s no doubt navigating the Providence Park pitch is second nature to him, that he knows how to move in any element, with any amount of sunlight (or not) covering the turf. Being on the field there is about as close to a second home as he can have. In any situation, he just does things already calibrated to the field, without thinking about doing them, leaving his brain free to process the malleable variables when other people are involved.

The same can be said of Mitchelldyer, who first shot at 1844 SW Morrison Street in 2003, when he was hired to shoot for the Portland Beavers, who happened to also own the A-League Timbers, when both teams played at what was then PGE Park. Though his tenure began focused on the baseball side, what started as headshots for the 2003 Timbers and covering about 14 home soccer matches in addition to his baseball duties—not to mention his outside job working for the Community Newspapers group—morphed into a soccer gig. “Every year, it just became more and more.”

Mitchelldyer’s time with the team is old enough to drink, and over those two decades plus shooting Timbers soccer, the home location has changed in shape several times. But it’s the experience and attention to detail that prepare him to be ready for the unpredictable drama of the sport.

“One of the things I love about soccer is when a goal gets scored, it’s very chaotic, and you never know what’s going to happen after the goal gets scored, or what kind of goal is going to be scored,” he said. “It could be a mundane shot that probably should have been saved and trickled in. It could be a crazy bicycle kick. It could be an Evander free kick golazo” [as we saw that night]. What type of goal, if there is a goal, and what happens immediately after that is not predictable, for players, fans, and photographer alike. But, like the players who train for their careers, Mitchelldyer prepares and does his homework.

“I go back and I watch,” he says of the games. “Because I’m looking at the game through a lens, I don’t always see the game as everyone else sees the game, I see in a very narrow point of view, one person at a time, whoever has the ball. I don’t get to see the whole entire thing. So I’ll always go back, and I’ll watch the game, I’ll watch the goals, and I’ll watch the highlights.”

There’s more to what he discovers discussed in our podcast interview, but one thing he noticed that explained our two main positions that night is “a tendency of the players, more often than not, to celebrate a certain direction… . [M]aybe they run to the person that gave them the assist, or maybe they run to the side where the bench is, or maybe they run to where their family members are sitting,” he said trying to make sense of the evidence. “Nine times out of 10,” he noticed, they go to the left. “So, for example, at Providence Park, if they’re going to the south, all of their families are [to the left of goal], and then going on the North End, a lot of times they’ll run towards the bench because the guys are warming up, and they all want to celebrate together.”

Because of this recent research, we set up where a goal was 90% likely to be celebrated: left of goal each half. Below, the picture on the left shows our first-half primary post-up, and the picture on the right, where we spent the entirety of the second half, as the team attacked toward the Timbers Army.

In this specific match, because of the quick two-goal lead St. Louis got out to early, Mitchelldyer felt confident that we could move a little and try some things. There was plenty of time left in the match, and the next Timbers goal would not be the tying Timbers goal, so there were a few opportunities to try some different things without the pressure of needing to catch, say, the first goal if the game is 0 - 0.

[It should be noted Mitchelldyer still caught all of the Timbers goals, and, even when we moved around, and the score changed, he assured me the team would catch St. Louis, that there were plenty of goals out there. Portland was not going to lose this game. He was right. And this feel for the game is essential to telling the story of the game.]

Our major move in the first half had us leaving our field-level position and walking up a few flights of stairs for a different look. From there, he caught the 39th-minute Rodríguez goal and kept an eye on b-roll potential that could be of use to his team in the future.

“We ran up the stairs, so I could get some kind of overall beauty shots of the stadium,” he explained of the move. “I also like to shoot from up there sometimes too, because with the longer lens, it gives you kind of a different perspective of the game and, speaking of clean backgrounds, the background is just the field, so everything's really clean, and it gives our graphic designers places to put text and make different graphics with it.”

Another thing I noticed is that he kept pointing his camera to the sky at seemingly nothing at all. When I asked him about it, thinking I’m simply seeing things that are not happening, he gave an explanation that makes perfect sense.

“There’s a certain window of time where it’s blue hour,” he told me, “where the exposure in the sky matches the exposure in the stadium. And so you can take a picture [where] you see the whole stadium, the lights of the stadium, and then you can still see the sky; it’s not pitch black, but it’s not really bright. It’s this perfect dark blue color.” The juxtaposition of sky and stadium makes for a great shot.

6: Gatoring

To be clear, that’s not a professional photography term (that I know of). It’s just the best way I can describe why my notebook from that night is blank from the 46th minute to the end of the match.

At halftime, as the Timbers would return to attack toward the North End, we moved one remote camera, so the east side of the field was covered at field level (see: “so much depends / upon / a yellow camera / remote”) and crowd level (see: “Soylent Green (and Gold) Is People, Part 1”), allowing us to sit as undetected as we could on the west to cover that side.

For the entire second half, we sat a couple of yards off the bench-side sideline, perpendicular with the 18-yard box. I just watched and took it in, waiting to see what different he’d do. Mitchelldyer did the same, waiting for what he needed. It was patient, but calculated, educated hunting

I later mentioned to Mitchelldyer that I was fascinated that we hung out there for the half, in that one space. “You make it sound like we didn’t do anything,” he joked. But we did, and I knew from all I’d seen to that point that the spot was intentional, that lying in wait was the best way to go.

“There are a couple of reasons for that [location],” he explained. “One, that’s where the Ethernet cable was. So I tethered into that cable. Two, I like to sit at the top of the 18, because a lot of times…Pipe’s second goal [which closed the gap to 3 - 4] is a great example of this. They might turn back around and start running back towards the center circle, right? So, if I’m not at the top of the 18, when they start making that run back, if I’m behind the goal, they’re running away from me.”

“And again,” he continued, giving credence to all that’s going on below the waterline of what I observed, “the reason we’re on that side is because we’re now next to the bench; we’re on the left hand side of the goal. My experience tells me that typically, they’re going to run to that side, which happened on every single goal of that half. So it ended up being the right decision.”

So, we sat. And we watched, a partial list of what went through Mitchelldyer’s mind goes like this:

If we score, and they go X direction, what am I going to do?

If X happens over there, what am I going to do?

If the light changes, what am I going to do?

If player X comes on, where am I going to shoot from?

If we go down goals what’s going to happen?

Who’s getting subbed on, what changes are we making to the formation?

Etc., etc…

It’s a constant process of What Ifs juxtaposed with what he knows from years, from that season, from that match. “A million different scenarios run through my head,” he said of our gatoring, “and sometimes I’m able to execute what I have in my head, and sometimes I’m not.”

One of those is the 100th-minute equalizer that happened right in front of us. “In my head before the free kick,” he said, “I was like, okay, I’m going to go to my wide angle camera if he runs this direction. But I kind of held on him a little bit longer than I should have with the long lens, and I didn’t switch to the wide lens as fast as I had told myself I was going to, so I didn’t get the wide shot that I wanted from that moment, but the stuff on the longer lens still looked good.”

A fair consolation. “[It was] of one of those, like, I talked to myself about what I was going to do, but I didn’t do it in time, because it was happening faster than I maybe anticipated, or something like that.”

These are the type of things that keep players, coaches, and photographers alike up at night. “We were at the top of the 18,” Mitchelldyer said of Evander’s goal, “and I wish I was in the corner by the corner flag, because he ran right to the corner flag and karate kicked the corner flag. If I was in that corner, I would have gotten a really cool picture. But since I was up at the top of the 18, I was on the side of it a little bit more, and it wasn’t as cool. So I think I might end up just sitting in the corner the next game, just hoping that they run to the corner.” He continued, “but then also on the other side of that, if Evander would have ran to the opposite corner, we had that remote.”

All things considered, my untrained photographic brain feels pretty good about what Mitchelldyer did catch:

7: Too Bad He Couldn’t Use It*

In a perfect world for Soccer City, USA, the Timbers don’t run out of time, the 5th goal comes, and all 3 points are secured. Certainly it was possible, it was nigh. But not all went as wanted.

That’s soccer. That’s life. That’s Craig Mitchelldyer’s profession trying to tell the story of both.

You prepare, you do all the work. You’re ready for luck to add the last element. It happens. Then VAR adds its verse.

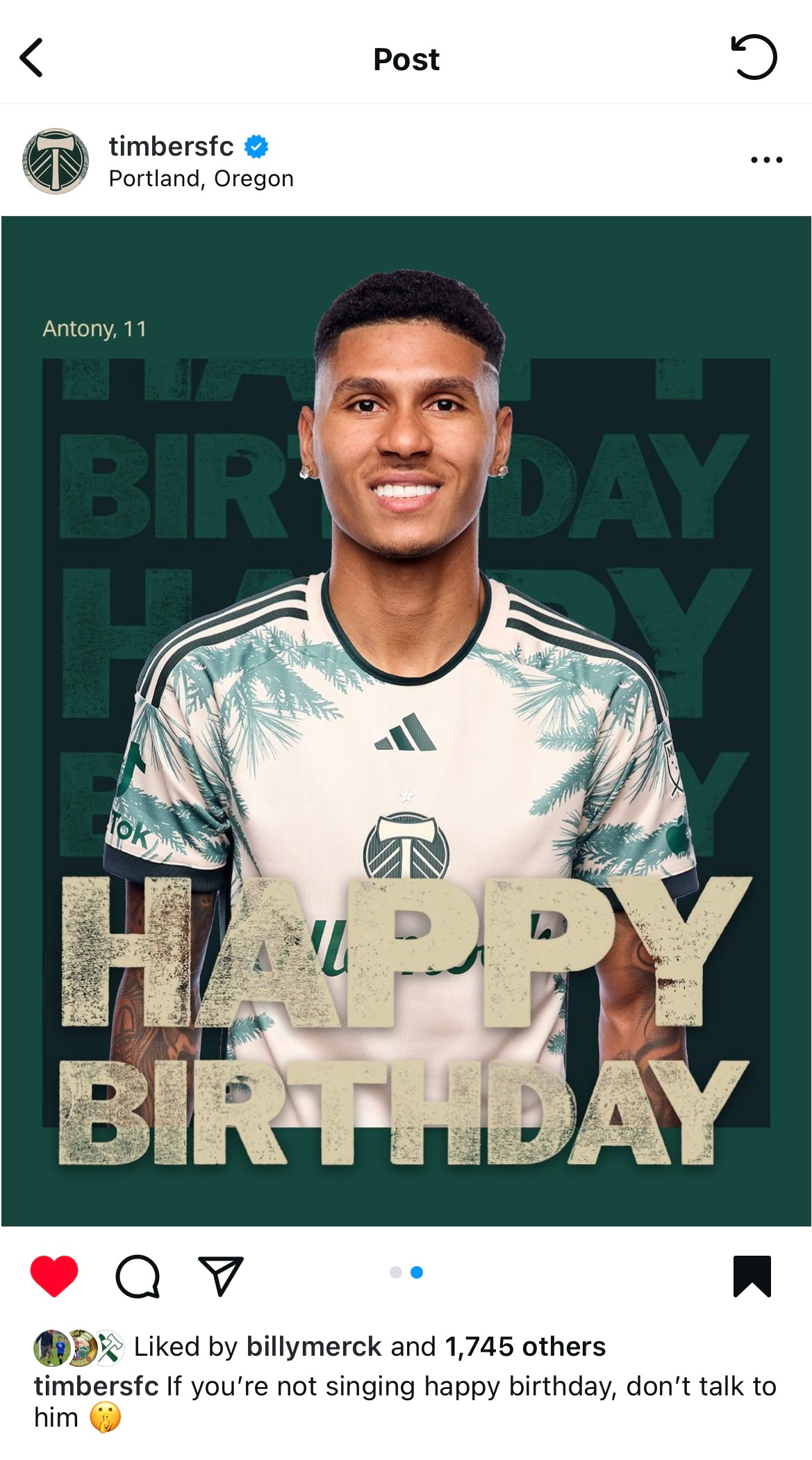

Antony’s called-back goal would have told so much of the story that night, and everything Mitchelldyer did to be in the right place, at the right time, coalesced if only for a few minutes. “It was a great celebration,” he said. “[Antony] ran right to me. I had the right lens on. You can see the crowd. [In] the picture you can see him with his arms stretched out and everybody else running behind him, it’s great. I think that if the game would have ended on that goal, that would have been photo of the night.”

From my Craig-adjacent perspective it looked like this as Mitchelldyer got the shot:

In our interview for the podcast a couple of days later, he seemed to have reconciled the reality. “You know, that’s one of those photos where we’ll use it for something somewhere sometime,” he said. “Even though it was a called off goal, it’s still a cool picture. So it’ll get used somewhere, sometime. But, you know, just not that night, because the goal got called off.”

Prophecy turned reality two weeks later.

Mitchelldyer messaged me on Instagram, with the team’s two-panel birthday-post tribute to the now 23-year-old Brazilian.

His message: “A use for a photo from the goal that wasn’t.”

8: In the End**

It’s not possible to cover everything I observed from one night in this space, even with this long of an essay AND the podcast interview. Even if I could, that wouldn’t be enough. Not 30,000 steps, not 10,000 photographs, not 8 hours at Providence Park following one of the best in the business.

Part of the problem is that Mitchelldyer has done too much over 30 years to get everything here. I have to admit, having seen all of this, I appreciate each image I get from the Timbers media even more because I know the craft and love behind it.

But the other part of the problem is that Mitchelldyer never stops trying different things, and that means preparation and opportunity never stop conjuring luck. We never stop getting art from the effort.

After his September 8 message pointing me to the Antony birthday celebration post, I thought I had it all. Then, on September 24, I see he’s up to this, a roughly 1,200-frame series of unedited photographs that present like video:

Then, three days later, the team took a trip up north to battle Vancouver. That yielded this September 27 post, showing the video of the shot and the shot itself:

Then, another three days, and Mitchelldyer is shooting the Portland Trail Blazers media day and finds “a random mirror” somewhere in the 63-year-old Veterans Memorial Coliseum, and the following ensues:

When the Timbers returned home October 2 to face Austin FC, I was finally getting my head around everything and feeling confident in the story I wanted to tell, that I could articulate enough of what happened to happen in my time shadowing Craig Mitchelldyer to share how this one part of our time at the stadium intersects, through one person’s career, to help us show who we are as a club…

Then, just before kick-off, as I settled into my seat in the Providence Park press box, I made the mistake of looking down to the field, where I saw Mitchelldyer with a fisheye-lens camera on a monopod, heading toward the team huddle.

#RCTID