Hvala Hrvatu (May 2023)

None of this happens in a vacuum. Pick your era(s) and take yourself to 1844 SW Morrison St. Whether Civic Stadium or PGE Park or Jeld-Wen Field or Providence Park, you can’t be there alone. You’re with teammates, with friends, with family. All of us, going there for the same reason, over the past half-century, do so together.

And this matters because habits become rituals, traditions; we find we belong there—to the place, to the game, to the team. To each other.

What does it mean to say RCTID? For every person you ask, you’ll get a differently worded response, all of them really saying the same thing: to be part of and love something bigger than ourselves.

It means we get to use that first-person plural. We support each other; we have each other’s backs. We make each other better. That’s our creed. What happens to one of us happens to all of us.

So when Dario Župarić celebrated his thirty-first birthday earlier this month, and all Major League Soccer gave him that day was an “undisclosed fine,” I took that personally. It wasn’t good enough for our teammate; it wasn’t good enough for us.

To right that slight, this month in Green Is the Color we celebrate how one Adriatic republic’s diaspora fits into our story—from our first goal this month to our first goal as a franchise.

Once in a While

Some cats are cut from a different cloth. Ron Futcher only played the ’82 season for the Timbers, scoring the franchise’s last goal, one of his NASL all-time fourth-best 119. For a previous essay, he let me in on the secret to his finishing prowess: “Stick your head where no man should ever stick his head.”

I’ve always preferred the assist, myself: a well-placed pass that beats a defender or two to help a teammate score a goal. That brings me joy—I’m a passer before a shooter. But I also understand that beast which is the goal scorer. It’s a different wiring of the same thing. So when Portland’s all-time NASL goal and assist leader, John Bain, told me for last month’s essay that when it comes to assists or goals, he prefers “scoring goals, without a doubt. There’s no question” I got it. And when Original Timber Tony Betts added, “To score goals is the best thing,” I thought, fair enough.

But a goal or assist—or any other moment that evokes emotion—happens only because of everything (and everyone) else enabling it. It takes all of us doing our thing.

After the May 6 Austin match, Dario Župarić said he preferred the blood on his arms and jersey to the goal he scored; that he liked the fight, the battle. “I hope the next game is [going to be] the same,” he said. As I’ve thought about this essay and this project, I’ve found myself realizing Župarić is exactly the guy I see the NASL Timbers players wanting to play alongside. He’s foundational for the team, and in his professional career he has evolved, adapted. He’s most interested in one thing: Doing his job so those around him are free to do theirs.

“I don’t care about my goal,” he said. “I don't like scoring goals. I like to keep zero on my goal.” All of this is above-board Župarić, a professional’s professional. Yet I can’t let go of the goal. And, of all the things he said after that match, it’s the one he said to the collected press as he left the room that sticks with me most: “See you guys in three years.”

It’s easy to dismiss that as an offhanded quip about press conferences. Though one wouldn’t know it—Župarić, after all, just held the room for a good five minutes with honesty, self-deprecation, and professionalism—in three years here, it was his first post-match press conference, and all could assume he’d actually prefer it not occur again until 2026.

A deeper dive, however, reveals the Županja, Croatia, native’s math matches his wit, and there just might be truth to the pattern of the center back’s consistent history of triennial scoresheet contributions.

On first glance, the reference could be to his previous goal, the 2020 MLS-is-Back Tournament winner. And maybe it was. But then I went back three more years and found two other significant goals. Then, three more to find another. And then three more to 2011, to the start of his professional career, where I found another.

I feel fortunate to have played professionally. I have no doubt in my mind—and this is a massive motivation behind this Green Is the Color project—that a significant reason I got to was because the NASL in Portland ended when it did, and those players who came here to play and build the game turned their attention full time to the latter. Soccer was still a new thing here in the ’80s, but the access I had as a kid to the soccer environment built by John Bain, Clive Charles, Tony Betts, Brian Gant, Bernie Fagan, Jimmy Conway, Bill Irwin, Willie Anderson, Mick Hoban, and so many others is the reason we have much of what we do today in soccer. They are the foundation, the culture.

In European countries, it’s both different and the same. Clubs are geographically closer; there’s more history; the sport is shared and ingrained in more generations. It is also, in short, more accessible. “It’s easy to train every day, to find a club,” Župarić told me of his youth experience. “But it’s not easy to play professionally. We start to play at 4 or 5 years old. Every town has a club.” In a country of just under 4 million people, the Timbers’ center back said, “90% of men would like to be professional football players.” Given Vatreni’s recent success internationally, I can even see that being a low estimate.

This shared desire creates an environment where a professional career—let alone one like Župarić’s that’s over a decade long and counting—is an impressive realization. “From youth, every training session, every day, you have to fight,” he said. “In Europe, if you lose a game, for seven days, you cannot sleep.”

As a fan now, I sometimes forget how much had to happen to get any player—to get us—to the 90 minutes we share on Saturdays. And this one, where Župarić connected on Evander’s cross at Providence Park, started 12 years and 5,700 miles ago in Vinkovci, Croatia.

In 2011, 18-year-old Dario Župarić signed his first professional contract with childhood club HNK Cibalia. In a 2011 Sportin Vigesti (translated to Sporting News) article, Cibalia coach Stanko Mršić assessed Župarić as “excellent when it comes to playing backwards; he just needs to improve his forward play and at least score a goal once in a while, because he has the potential for that.” Taking his coach’s words to heart, Župarić scored his first professional goal that season, his only in 58 appearances for Cibalia.

Three years later, on March 14, 2014, “once in a while” came again, as Župarić scored on schedule. This time, it was for Pescara in a 2-0 win over Cesena, his one goal in 99 appearances for the Serie B side, which he joined from Cibalia for a then-record 700,000 Euros. True to form, it’s the other contributions that helped him elevate his teammates—and his club, as Pescara earned promotion to Serie A in Župarić’s tenure.

Then there’s the once in a while that happened twice (you guessed it, three years later) in 2017, with his next club HNK Rijeka that lands. When Župarić started that 2023 post-Austin press conference, when asked about his thoughts on scoring the first goal of the match, he said, “I didn’t know how to celebrate.” That statement was, I assume, meant to break the ice, more self-deprecating than true because, on May 21, 2017, in the 72nd minute of a Croatian Football League match, Dario Župarić headed home a corner while playing for Rijeka, putting it up 4-0 against league opponents Cibalia. The goal not only secured full points, but the historical significance of its ramifications was immense. With the win, Župarić’s club—in its 110th year—secured its first Croatian Football League title, its only one to date.

[For context, since the league’s inception in 1992, Dinamo Zagreb has won the league 24 times. Hajduk Split: 6 times. NK Zagreb once. Rijeka has only won the league one time: that 2017 season.]

It was and still is a massive win for a historic side. Everyone associated with Rijeka rightfully understood the gravity of the moment and celebrated. Everyone but the goal scorer. After the ball hit the net, Župarić signaled to his teammates to stay calm, and he walked with a muted understanding of the moment. “We won a championship for the first time in history,” Zuparic told me about the match, “but [Cibalia] was my first professional team. I didn’t want to celebrate.” In the huddle of hugs after the goal, Župarić can be seen at least smiling, but outwardly the professionalism and respect toward Cibalia speak volumes of his character.

Ten days from then, in Zagreb, he did get a chance to explicitly celebrate a goal. Again in the 72nd minute, again from a corner, the Rijeka center back turned home a bouncing ball with his left foot. The goal put his side up 3-1 over Dinamo Zagreb in the Croatian Cup final, securing the first (and only to date) domestic double in Rijeka history. In a celebration that should look familiar to 2020 Timbers fans, Župarić ran to the corner, slid on his knees, and was mobbed by teammates—those on the field and reserves alike. “Yeah, I did celebrate that one,” he told me with a smile on his face. So, yes, he does know how to celebrate. He just also knows when it’s appropriate.

And it’s apparently appropriate on the three-year timeline because he did it again in 2020, also from a corner but this time in August and with Portland and in the 66th minute, when the Diego Valeri cross found Eryk Williamson, who shot toward goal, where Jeremy Ebobisse tried to redirect, and the ball found Župarić who tapped in what would be the match- and Tournament-winning goal. Like above three years ago: Župarić ran to the corner, slid on his knees, and was mobbed by teammates—those on the field and reserves alike.

Personally, that goal meant a lot to me, as I assume it did to you, too. On the surface, as a fan of the team, to see only the second Croatian Timber in history score, to see something positive and aptly prideful come at a time when nothing was normal, when watching this team compete on TV—even “in a bubble” in Florida—gave me great pride and, as important at the time, a sense of normalcy. That’s the anchor that sports (and a player like Župarić) are at their best, as they tether us to experience and emotion that can hold all the other things together. MLS was “back,” and sports were “back,” and that helped with just a little hope that everything would again be back.

And now that things pretty much are, we can put Župarić’s first Timbers goal—and the championship that came with it—in perspective: there’s only going to be one MLS is Back champion, and that’s the Portland Timbers. There’s only going to be one MLS is Back tournament-winning goal, and that was scored by one of us.

“I was really happy because I signed just four months before,” Župarić said of the 2020 goal. “It was my first with the Timbers,” and that was why it was special.

So three years from that goal, when I was able to sit down with him after training, his first one-on-one with an outside reporter here and my first one-on-one with a current player since I’ve been on this project, I reminded him of something else he said in the post-Austin press conference. “You said you don’t like scoring goals,” I told him. We talked about the two with Rijeka, the two with the Timbers. “But of the last four,” I asked, “which is your favorite?”

“Yeah, I only score in big games,” he said with a laugh, “only when we’re playing for trophies.” Župarić cataloged these four goals, “This goal [against Austin] is special because it’s my first one in front of the [Timbers] fans.” He was quick to note the larger context, that, in the end, the win would have been more important. But in thinking about the others, all landed: Croatian Cup-winning games, first for the Timbers, first at our home. “But,” he said, “I cannot choose one of the Croatian finals, MLS is Back, or this one.”

For those who would say this one wasn’t for a trophy, there’s one contemporary counterpoint: Not yet, but, at the end of the month, Portland ended in ninth place in the Western Conference, just above Austin for the last spot north of the playoff line. The two teams were tied on points and wins (the first tiebreaker). The difference that separated the two was the second tiebreaker: Goal Differential. The Timbers were one (Župarić?) goal ahead. One goal.

“I only score in big games.”

Enter the Dragan

Sometimes things that start out well don’t end as such. But good things can come from that, too.

The Timbers followed the Austin match with a 3-4 Open-Cup-exiting loss at home, a high water mark for May in a 3-1 Cascadia Cup dismantling of Vancouver, then a 0-0 draw away and two losses, the final of which didn’t feature the Timbers’ Croatian center back because he was out serving a yellow-card-accumulation suspension. “In my professional career of 11-12 years,” Župarić said, upset he couldn’t be with his team. “I’ve played almost 100% of the games. I always play. When I have free weekends, I don't know what to do.” I felt for him. I’d rather have had him out there, too. But rules are rules.

In the NASL, there were some fantastic rules meant to build the game in this country. The 35-yard offside line is one. That opened up the field to give forwards more room to be onside closer to goal, an idea meant to increase scoring to bring more (uninitiated, American) fans to the game. The NASL tried a few things: Playoffs, 10 points possible per match, a 35-yard shootout for matches level after overtime, and a minimum number of North Americans on the field.

It’s that last one that brought Portland its first Croatian-born player.

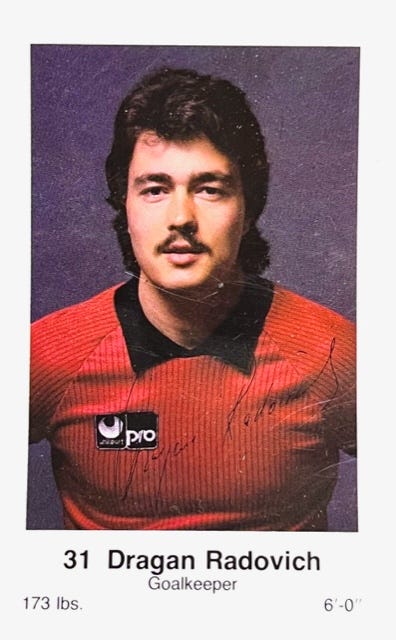

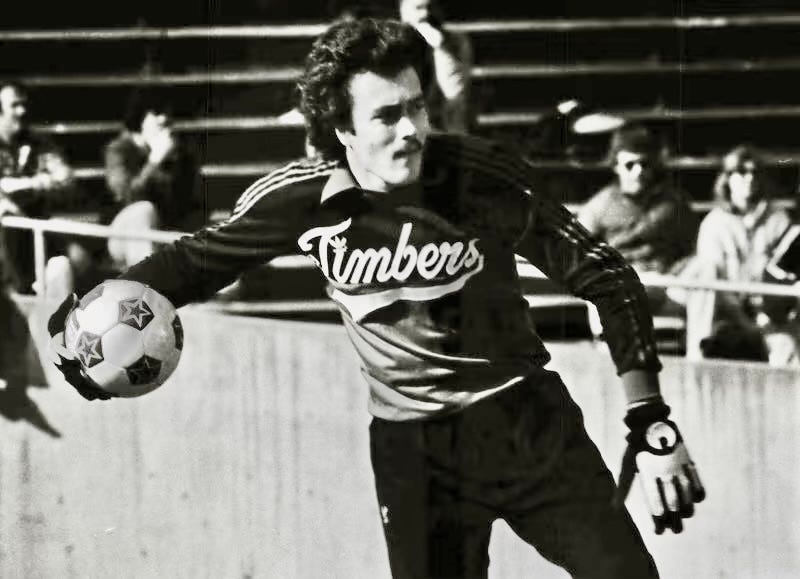

On May 2, 1981, in the 63rd minute of a 1-3 loss to Tulsa, Šibenik, Croatia-born Dragan Radovich became the first—and, until 2020, only—Croatian to play for the Portland Timbers when he subbed on to replace the Scottish Kieth MacRae. Radovich—who moved to New York at age 11—was also North American by citizenship, so when Portland coach Vic Crowe had to replace Bernie Fagan (who became a U.S. citizen in 1980) with Irishman Jimmy Kelly, Radovich was necessary to make a third required North American on the field. “I’m confident in Dragan,” Crowe said after the match, noting he’d feel fine tabbing Radovich when needed.

According to teammate John Bain, Radovich was brought in that ’81 season “as a backup for Kieth MacRae, but [Dragan] ended up splitting time with him.” Bain remembered netminder Radovich as the type of presence one would want from someone holding down the back: “Really laid back, calm, very solid, good with his feet, didn't make mistakes.” The first three attributes Bain remembers of his off-the-field personality as well.

And what’s better than one Croat on the field?

Opposite Radovich, in Tulsa’s goal that night was Željko Bilecki—a Timbers fan’s should-be favorite (See “No Pity Land”). Like many NASL players of the ’70s and ’80s, Bilecki followed the franchises that survived, which also means he was present for quite a few significant moments in league history, like in 1976, when Toronto Metros-Croatia won the second-ever Soccer Bowl—Bilecki was in goal.

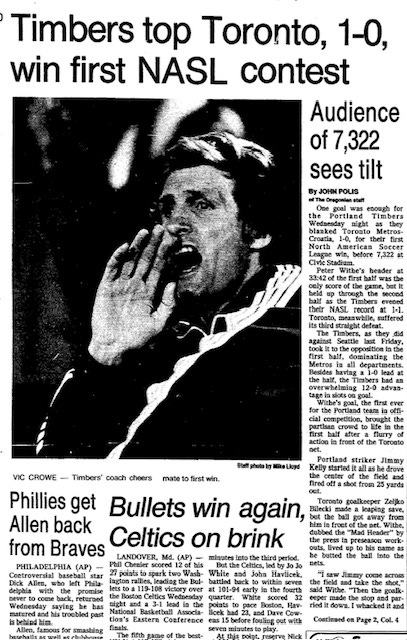

Here’s the main reason we should know his name: The Zagreb-born Bilecki, Croatian by birth and eventually Canadian by citizenship, never played for the Timbers, but he holds a special place in our history. On May 7, 1975, Bilecki was minding the Metros-Croatia net when Timbers’ Peter Withe scored the franchise's first goal in its first win. “Withe, dubbed the ‘Mad Header’ by the press in pre-season workouts,” The Oregonian’s John Polis wrote, “lived up to his name as he butted the ball into the nets” (sic). The 34th-minute goal came in Portland’s second match of the season, a 1-0 win at Civic Stadium in front of 8,500. So, Hvala, Željko Bilecki; even when Croatians are Canadian, they’re still there for us, right from the start.

But in the end, there was Dragan.

In 1982, Radovich and Bill Irwin (the Northern Irish international who became a naturalized U.S. citizen in March of 1981) battled for duties, much as they did in the dying days of the Washington Diplomats where Radovich backed up Irwin—this time doing so free of the constraints of citizenship.

“Yeah, Dragan was a decent goalkeeper,” Irwin said of his two-time teammate. The two were at different ends of their careers at the time. When Irwin went down with a season-ending ankle injury toward the end of ’82, the season, and NASL era, were Radovich’s to bring home.

Portland’s last NASL win and shutout came in a 4-0 drubbing of the Edmonton Drillers, a home match on August 18, where John Bain scored twice; Radovich posted his third shutout in a row; and, in the 83rd minute, Ron Futcher slotted Portland’s last NASL goal.

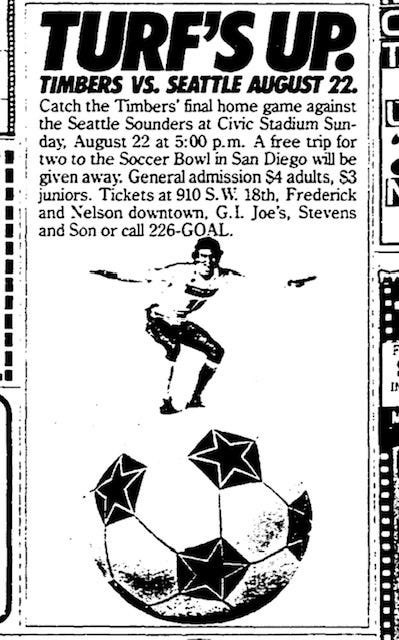

Just four nights later, the NASL Timbers era ended as it started, with a 1-0 home loss to Seattle. The Sounders’ match-winning goal came at the 85-minute mark, ending Radovich’s shutout streak of just over 364 minutes and ending what would be the NASL Timbers. “It’s especially hard,” Brian Gant told The Oregonian's John Nolen, “because this could be the last time together for these fellows—forever.”

Gant was right, to some degree. Here we are together now, moving forward, keeping it all together through story. And that’s the spirit behind Green Is the Color.

I have not been able to track down Dragan Radovich—yet. There’s more than one New York phone number that I think has blocked me, but I’m going to keep at it. He is, after all, one of us. So, I’m adding Dragan to the roster of must-finds with Mr. Kick It! [EDIT: See Podcast Episode 7: Dragan Radovich.]I had a break in that search, in the form of an alumni association director who informed me, “It looks like Mr. Olson is still with us.”

As long as we keep sharing our stories, they all are.

A Canadian and a Croatian Walk into a Park

When we go to games, we bring our stories with us. At a given home match, that’s over 25,000 of us with different histories, watching and reacting together to what happens with one ball.

For Timbers and Thorns games, Brian Gant sits with his wife on the west side of Providence Park. In 1982, however, he climbed atop a 5-foot soccer ball for you. “I really had to balance [up there],” he told me of the shoot, which predates photoshop, meaning he actually had to be there, on that ball, “while a couple of workers tried to hold the ball in place,” he said. “‘Turf’s up at Civic Stadium’ was the saying while a version of the Beach Boys ‘Surfing USA’ played in the background.” That ad, shown above for the last Timbers NASL match, is both a lasting image of a bygone era and a testament to the lengths Gant and his contemporaries went to build soccer here.

On the east side of Providence Park, Jack Ubik works in Tanner Ridge. I met him in the 2022 season, when some friends gave my son and me their tickets. My then-9-year-old son was excited to go. He grabbed matching Timbers scarves for us to wear, and he picked out his preferred jersey: a 2015 Timbers’ red kit. I didn’t have a Timbers jersey and reconciled with a relatively esoteric move: a 2006 World Cup away Croatia blue, with my grandmother’s surname, Babić. My son accepted the choice; after all, we’d been talking about Župarić and had, in January of that year, applied for our Croatian citizenship through that Babić lineage.

To Providence Park we went, and when we ascended the steps and walked onto the concourse of Tanner Ridge, we were greeted—as most new to the level are—by Ubik, who is the lead usher. “I mostly provide a public relations and managerial function,” Ubik told me in an interview for this piece. “For newcomers, I explain the amenities that come with their ticket, so they know what they can access.” We’re in good hands with Jack.

But that first visit, for me and my son, included a unique Ubik greeting, directed mostly, I assume, at my kit: “Kako ste?” he said. The Croatian formal “How are you” surprised me momentarily, and we had a quick chat about our similar Adriatic lineage—in English, as we’d both exhausted the conversational Croatian we each knew shortly after our greeting.

The match itself was great, with the Timbers coming from behind to beat San Jose 2-1 on goals by Niezgoda and Asprilla, green smoke coming from the North End and time spent sharing the moment with my son.

Later, at the end of that 2022 season, as I was exiting Providence Park after the last home match’s post-match press conference (See: “Wherein the Quest Begins”), I again ran into Jack, who was working the last gate open, Gate F. This season, as I got into this project, I made it a point to catch up with him, and I found a lot more in common than remedial use of a Balto-Slavic language.

Jack’s favorite Timbers (current and historical Diegos aside) are Dario Župarić and Jarosɫaw Niezgoda, which makes perfect sense given he grew up in the Chicago neighborhood of Hegewisch to a Polish father and Croatian mother. “My dad's family,” he told me, “lived at the end of the same block in Chicago that my [mother’s] family lived on. And then, when my dad and mom got married and began to have children, we lived on that same block. So we never left the block, let alone the city.”

Jack’s path that makes Portland (and Providence Park) home, however, is like Gant’s and so many I’ve met: not their first home but their current home, and the Timbers are a major anchor of what that means. But there is also a layer of what they’ve passed on to next generations in their stories. When Ubik was a college senior in Indiana, a friend wanted to attend a job fair where Los Angeles schools were hiring. “I had no interest in L.A.,” he recalled, “but I wanted the interview experience.” Jack got a job from the interview and decided to try L.A. for a year because he’d not been West before. He ended up not only loving L.A., but staying. “As one thing led to another, I never went back to Chicago. My one year came, and by the end of that I had made new friends in California. And then I ended up staying there and teaching in the Los Angeles City Schools for about 10 years.”

During that decade out West, Jack met his would-be wife, a Beaverton, Oregon, native. In 1974, as they had kids of their own, they moved here to be close to her family. They never left.

Being here meant being in the right place at the right time. While Jack was teaching at then-Wilson High School, the vice principal had been attending a basketball banquet one March. “He was sitting with others on a raised dais,” Jack recalled, “somebody cracked a joke, and he fell off and became incapacitated, aggravating an old football injury.” The principal at the time tabbed Jack to take over the role, and Portland Public Schools was where Jack remained in administration until he retired in 2003.

We don’t know where our future selves will end up, but we do know we can give back, can make where we are a better place, especially when we look out for each other through what we have in common.

When the NASL ended for Portland in 1982, some guys went to seek their fortune with other outdoor sides and indoors. As a league, the NASL only lasted only two more years, and many of those former Timbers returned here to coach. “I still coach today because I love the game of soccer,” Brian Gant told me for a previous essay about Clive Charles. “I've always loved it. But I happened to get pulled along by a guy [in Clive] who didn't just love the game. This game was his life. I saw what he did, and I went, ‘Wow.’ I started seeing how I was being influenced and how I was influencing the kids I was coaching. I was like, ‘This is great. It's so much fun.’”

Gant recalled a conversation he had with Charles that mirrors Ubik’s steady trajectory joining a love of teaching with making a specific place better than he found it. “I was teaching and coaching [at] Catlin Gabel,” Gant says of the time in the 1980s. After Charles had been at University of Portland for a few years, Gant remembers them talking about college coaching. “[Clive] said, ‘You probably wouldn't like coaching at college because you only coach the first few months of the year. The rest of the time you're spending recruiting and you're not coaching.’ And you know, personally, I love coaching. I'd rather not be traveling around the countryside asking kids to come to my school to play.”

Gant loved that he was able to teach at the school and coach. They’d just started FC Portland, and that with Catlin Gabel was the right spot for Gant, whose Catlin Gabel teams won 12 of the first 13 girls’ Oregon state soccer championships at their level, part of which was an amazing 11 in a row.

Ubik, as well, continued to contribute here after a career transition. Retirement didn’t jibe with him, and when talking to a friend back home in Chicago, who was an usher for the Cubs, Jack had a think and found a short-season baseball team opening shop in nearby Hillsboro. Much like the supposed one-year trip to L.A., Jack’s temporary try-it-out (“they were short season, which meant that they started in late June and were over Labor Day weekend. I said to myself, ‘That's a short enough season that if I don't like it, I can just finish the season out and not renew for the following year’”) ended up lasting longer than planned (“as it turned out, I enjoyed my experience immensely and had no intention of resigning. So I stayed with the Hops, and I'm still [there]. I'm one of three employees at that stadium that have been there since their inception”).

Given the nature of professional sports scheduling in Portland, Jack’s able to provide a similar role for the Hops, Blazers, and Timbers. It’s more than sports, however, as it always is. “The reason I stay,” he said, “is that during my time as a principal in Portland, I've worked with probably 7,000 to 7,500 kids. And every night, at every one of my venues, I have at least one former student come up and say, ‘Are you the Mr. Ubik that used to work at so and so?’ and then we have a nice long conversation on what they've been doing with their life. Which makes it highly enjoyable. For me, that's probably the main reason that I continue working.”

Brian Gant and Jack Ubik spend their games on opposite sides of Providence Park—Ubik in Tanner Ridge, and Gant in his west-side seats. But what they have in common is what they’ve given to the thousands who’ve walked into that stadium over the years, and the equally thousands of kids they've served in our community over the last half century.

And what they have in common is what we all do when we come to this team, regardless of where we come from or where we watch: We’re connected, for 90 minutes, for 50 years, by what we love. And we’ll do anything to share that and pass it along.

Fine aside, the first week of May was about as good as it gets for the Croatian diaspora in Portland. Tuesday was the 42nd anniversary of the first Croatian player taking the field for the Timbers; Wednesday, Župarić’s 31st birthday. On Thursday, my wife, son, and I found out we were approved for our Croatian citizenship, and on Saturday, in the 33rd minute of the match against Austin, Dario Župarić got on the end of an Evander cross and scored his first goal in front of the home fans. Sunday would bring the 48th anniversary of the Timbers’ first franchise goal, which came against our favorite Hrvatski foe (Hvala, Željko).

And at the end of the month, I thought about how those are all just external things. Great as they are, there’s something else that brings us together.

May 30 is Statehood Day in Croatia. It’s a day that, in part, marks Croatian independence from Yugoslavia. When I interviewed Dario Župarić earlier in the month and asked how he’d observe Statehood Day, his response was as honest and no-nonsense as he is. “I’m Croatian, and I love Croatia,” he said. “You have to love your country, and that’s it.” He told me how much he loves it here also, and I get the impression it’s all the other things in the moment that make him tick: playing the game, helping his team, being present every day. It’s not just once a year (or once in a while) that he’s the Dario Župarić we’re getting to know; it’s every day.

That’s how it works when you’re part of and love something bigger than yourself.

So on Tuesday, where I was, I put out our Croatian flag and raised a rakija to the holiday, to the players who came before us. And to Dario Župarić, who rejoined his teammates at the Timbers Beaverton training facility that day, ready to prepare for June, for the Sounders. To play for Us.

What does RCTID mean? It means Mick Hoban to Noel Caliskan. It means that in 1975, something started here when those first Timbers came and did anything it took, gave everything they could as professionals—think about that: they gave their profession, their life’s skill—to build the game we love, the game we can now pass along, like a heritage, a nationality, a citizenship. And we do that not once in a while but every time we come together.

That’s worth celebrating.

#RCTID