Charlo The True (or, The Three Provides) [Pt. 2]

This is the second part of the three-part essay about Clive Charles: "Charlo, The True (or, The Three Provides)."

Part 2: Gary of Troy

Gary Osterhage has the head that launched a thousand ships.

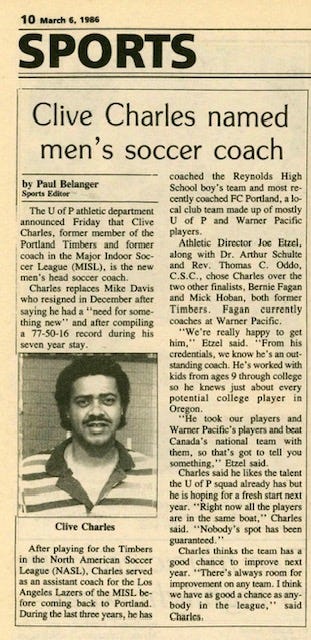

It happened October 22, 1987 in Portland’s Civic Stadium. Just before halftime of a match between the University of Portland and an undefeated Notre Dame side ranked seventh in the nation, Osterhage’s magic melon met a Joey Holloway cross to score Pilots’ game-winner.

He scored it in the stadium’s North End, in front of what would, in present-day Providence Park, be home to the Timbers Army or Rose City Riveters. But that night, it was the Portland Pilots faithful who made up most of the 2,074 in attendance. The moment: absolute poetry. With a touch of comedy.

On today’s turf, Osterhage’s post-goal knee slide into the corner would have had him gliding over the surface cleanly until a natural inertia took over. Thirty-five years ago, however, the stadium’s AstroTurf surface, the kind NASL Timber Willie Anderson succinctly called “terrible,” failed to provide the physics Osterhage expected. “I went to slide on my knees, you know, celebrate, but it was dry,” he remembered. “And so I didn't slide. I just stopped, and it ripped my knees up. I'm bleeding and all the guys are just laughing at me.”

Semantics mattered not to the goalscorer. “I was so jacked up,” he said. “I went flying by and gave Clive a hug, and he says, ‘Damn, that was a good goal.”’

It was a good goal. And an important goal. Not the first, but the beginning. See, Osterhage’s noggin knock netted the proof of concept second-year Pilots’ coach Clive Charles needed to build the program he wanted. It was all part of the plan.

In an article previewing the match, Charles told The Oregonian’s John Nolen, “We will keep going after [Notre Dame], even if we get an early goal… . We’re not going to lay back.” Portland’s Scott Benedetti’s finished just 37 seconds after kickoff, handling the first part of the prophecy, and that Osterhage header just before halftime brought the oracle full circle, giving the Pilots a 2-0 lead of what would become a 3-1 victory for the underdogs.

Yet it wasn’t about Notre Dame, nor was it about that one game. It was bigger.

The Irish were brought to Portland intentionally to test the Pilots. Then-UP athletic director Joe Etzel told The Oregonian's Norm Maves that the smaller, lesser-known (and American-fooball-less) Portland financially supplemented Notre Dame’s trip to make the game happen. “We’re making a conscious effort to be a regional and national team,” Etzel said, in support of his soccer coach’s grand plans. “So we’re trying to upgrade our schedule. Notre Dame was probably the most difficult to get, but we wanted them.”

That match was the watershed moment of a massive culture shift at the center of Charles’s plans. “I had to try and change everybody's thinking from trying to be competitive on the West Coast to being the best in the country,” Charles reminisced to Gregory Dorr in “Man of the Match,” a 1998 article in Portland Living Magazine. “First of all telling my players that, and secondly trying to explain to the school that that is something we could do. Everything that I did, the reason for doing it was because this will make us the best program in the country.”

It was one thing for Charles to have those goals, but he could never do it alone. One tenet that echoes from those who worked with him is true in coaching: you can’t want it more than your players. Charles was trying to build something special at the college, those people had to want it–even if they hadn’t seen it.

Charles believed in the vision. Osterhage believed. Canadian freshman Rob Baarts was on the field that night, and he believed, or he wouldn't have been there. Baarts had chosen UP over Clemson and the University of British Columbia. “Clive was trying to change [the program at UP], and I wanted to be a part of that change,” Baarts said. “Clive created this sense of family and being a part of something. He made me feel if I don’t do this, I’m going to miss out.” As good as that win must have been for the participating players, its intended effect was felt off the field.

“There was one game that Clive called the turning point of the entire UP story,” Joey Leonetti told me of the Notre Dame match. “I was there.” Leonetti, then a high school senior who would later that fall be named Oregon’s high school player of the year, wasn’t the only future Pilot impressed by the win. “Sammy Singer was there,” Leonetti said. “Sammy was being recruited as a left back from Northern California.” Singer was what Leonetti referred to as a “big catch” for the program reaching outside the immediate area: a California North ODP and Region IV team player from the national team pool.

“When you are going after the top players in the country,” Charles told The Oregonian’s Maves before the match, “you have to show them that this is the direction we’re headed, this is where we want to go. What this does is give me an opportunity to go ahead and schedule other top national teams.”

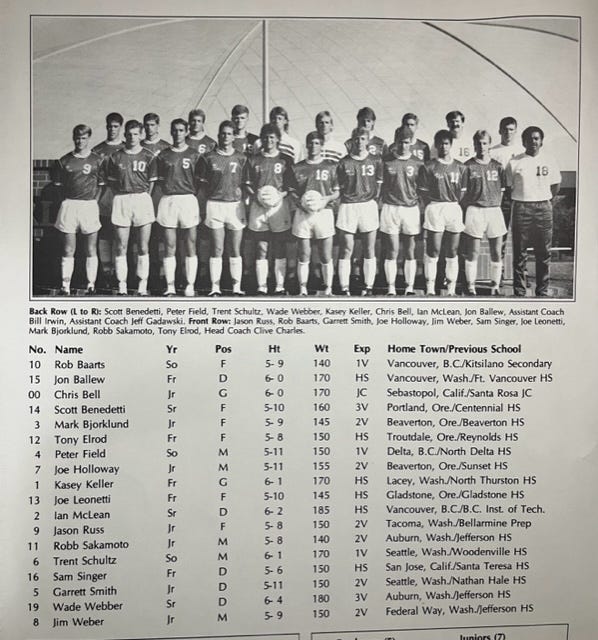

It worked. The next season’s recruiting class brought in seven new players. Joining Leonetti and Singer in ‘88 were Tony Elrod, John Ballew, would-be back-up GK Chris Bell, the best soccer player to ever transfer out of British Columbia Institute of Technology: Ian McLean—

and a freshman goalkeeper by the name of Kasey Keller.

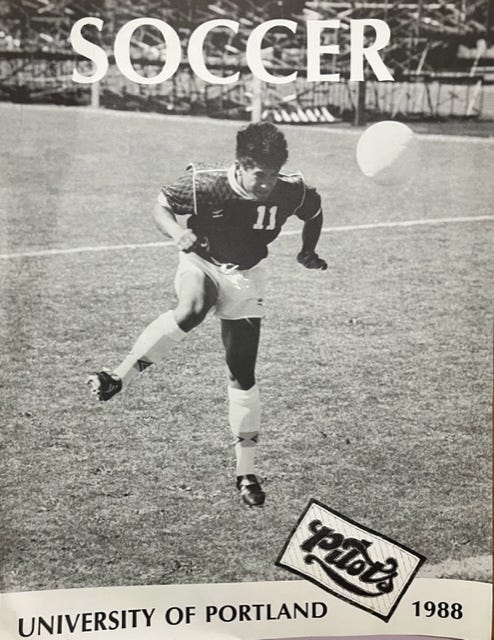

Clive’s 1988 University of Portland soccer team is still the best men’s team the university has produced. And though Charles never had a losing season for either the men or women, that third edition of his era is statistically very special. To this day, they still hold ten team records, including 21 consecutive wins, a streak that included a baffling 16 shutouts.

The summer before Clive’s first fall in charge, I attended my first University of Portland soccer camp, where I met then-player Jeff Gadawski. He was my camp counselor that week and he would be the next summer too. By the ’88 season, he had joined Clive and Bill Irwin on the coaching staff.

Gadawski’s journey to Portland was very ’80s college soccer. He was an Ohio state player of the year who used a calling card to phone one-year Pilot Brian Kohen, an Ohionan who had gone west to college. When Kohen told Gadawski that their goalkeeper was a senior, Gadawski eschewed other college offers to join the pre-Charles, Mike-Davis-coached Pilots.

After two years with Davis, Gadawski had a chance to play for Clive. When a knee injury redshirted him his first year, his second was spent splitting some time with Greg Maas. While dealing with his injury, Gadawski started coaching the Pilots JV team. For 1988, Gadawski could have redeemed his last year of eligibility. “But there was this kid named Kasey Keller coming in,” Gadawski said. “I thought it was best if I just went on the coaching staff.”

Something else was set in motion. For me, the camps with Jeff as my coach gave me a connection to soccer that was bigger than my experience. At 11, I was impressionable and interested in the game.

Just as essential to my experience was access. I had the luck to not just be falling in love with the game and getting to know a college player at the impressionable late-elementary-school ages but also to be living in close proximity to the university. Because of the camps, I felt connected, and I also found that the budding program meant there were always netted goals on the open fields. I spent hours dragging a bag of balls a few blocks to UP and playing until campus security kicked me off or my mother would send one of my siblings to fetch me.

Going to a University of Portland soccer match years previous was almost an accidental act. More than once, I remember my family driving by the college on our way home from somewhere, only to see there was a game going on. If I was able, I’d walk up there with one of my brothers to watch. There was no gate. The field was on an open part of campus, inside three quarters of a track. It was come-as-you-are soccer watching, and the best part was that spectators could sit as close as they wanted, a freedom fans enjoyed through the ’88 season.

On the field, the team just kept proving themselves and getting better. What started with the yes-we-can win over Notre Dame the previous year earned the team a proper test out of the gates the next season with the first two matches against national powers San Francisco and UNLV. “‘These are the most important games this school will play’,” Leonetti said Clive told the team of their first two matches. “And we’re just sitting there like, ‘OK, Let’s go!’”

Scheduling top teams right out of the gate fit the belief the coaching staff had in the players. “We owed it to the players to play the best teams out there,” Bill Irwin said. “We wanted to challenge them all the time.”

They met the challenge. Portland beat USF 3-0 and followed that with a 2-1 come-from-behind overtime win over UNLV. “From there, we felt invincible,” Leonetti added. They played like it, too, winning all 19 matches on their regular-season schedule.

It all paid off with a first-round bye that had the #2 Pilots hosting UCLA in the second round of the ’88 NCAA tournament. With the bye, Charles was able to scout the Bruins’ first-round match. “We thought Clive was going to come back and say we would have to change this or that,'' then-freshman Kasey Keller told The Oregonian’s Steve Brandon. “But he said if we just play our normal game, we can beat this team.''

And beat that team they did. On a soggy field, in front of 3,392 loud fans, it was a signature win of signature wins. I remember a few things about that game. Because it was an NCAA match, they had to charge admission. That’s the first time I remember ever needing a ticket to go to a game. Something else I remember is just how many people were there. The university had erected temporary seating that somehow held throughout the full match without collapsing. It was important to the school and players, but it was also a collective event everyone there could own. Not since the NASL Timbers closed up shop had that happened around soccer in Oregon.

Lost in the footnotes is that the Pilots would have to move forward without team-leading goal scorer Rob Baarts. The night before the UCLA match, on the way back to campus from a team dinner, the car Baarts was in was hit by a drunk driver, and he suffered the injury but remained coy. “I didn't want anyone to look at [my knee] in case there was something wrong and they wouldn’t let me play,” he said. In the second half, Baarts made it to the endline and delivered a ball to Scott Benedetti, who laid the ball in the path of Trent Schultz for the first goal. But the pain and swelling became too much in the last minutes of the match. After a visit to the doctors, the x-rays gave the news that ended Baarts’s season. “My kneecap was cracked.”

In the next match, a quarter-final at Fresno State, the Pilots handled the Bulldogs 2-0 but lost Wade Webber to a red card. The penultimate loss, however, was that of home-field advantage. In 1988, the NCAA finals were played at the campus of the higher seed, not a predetermined “College Cup” location, as they are now. At 21-0 and ranked #2 in the country, the tournament should have returned to Philbrook Field. The only problem: “We have no field because our field is torn to hell,” Joey Leonetti said about the reason the higher-seeded team had to travel to lower-seeded Indiana. “That is when the decision was like we're building a field. The momentum was there. This was just like a slap in the face; we can’t host the Final Four because we don't have the field.” Just under two years later, Harry A. Merlo Field opened.

Home or not, there was still work to do. At Indiana, the Hoosiers would sneak a soft goal in the first half, which was enough to give the Pilots their only loss of the season. “We played them off the park in the first half,” Jeff Gadawski said. “At halftime we went into our locker room and Clive noticed that the Indiana locker room was right next to us. Clive just comes in and puts a finger to his mouth like, ‘shhh, not a word.’”

Kasey Keller remembers the same. “We're losing one-nil on a deflected goal. And I remember Clive saying, ‘Hey, everybody, just be quiet. This is what you need to know, with how you played in that first half.’ You could hear through the wall, [Indiana coach] Jerry Yeagley going nuts on his players, because we absolutely played them off the park.”

“For the next 15 minutes, while guys are getting drinks, we just listened to Yaegley lay into his team,” Gadawski said. When it was time to go to the field, Clive said, “just keep doing what you’re doing.”

“Clive knew when he needed to have a go,” Keller said, “and he knew when we just needed to understand how well we played. That was one of those moments we played very well and were just unfortunate to be a goal down.”

Indiana won the national championship in the next match, their third in seven years. But for the Pilots, it was a massive step. “Obviously, we’re playing at Indiana, on their field. We absolutely killed them and just had one of those games we just couldn't score,” Kasey Keller said. “I truly believe if Robby [Baarts] was fit and Wade was on the field, we would have cruised to a national championship.” Yet the focus was balanced. That season, Keller said, “started the legacy, through Clive, through Harry Merlo.” Things were only looking up.

And in the moment, Clive knew, too. ”I’ve got a list of 10 players I’m interested in,'' he told The Oregonian’s Steve Brandon in the post-game interview, “and another list of about 500 players who are interested in us.''

Even now, as a fan, I can’t help but want that win. But the true magic of the moment is in what happened because of it. Like Rob Baarts, I’m still in awe. “What Clive accomplished will never happen again,” he said. “You just can’t go start up a new program and in a couple years build something like that.” Baarts has the unique perspective of knowing something about this, as a player and now a coach. He and 2005 UP graduate Miguel Guante are nearing their fifth year building a New Mexico State women’s program. And yet some would marvel at how Charles could have taken on the women’s team and built two successful programs. The truth? He didn’t.

He built one that had twice as many players.

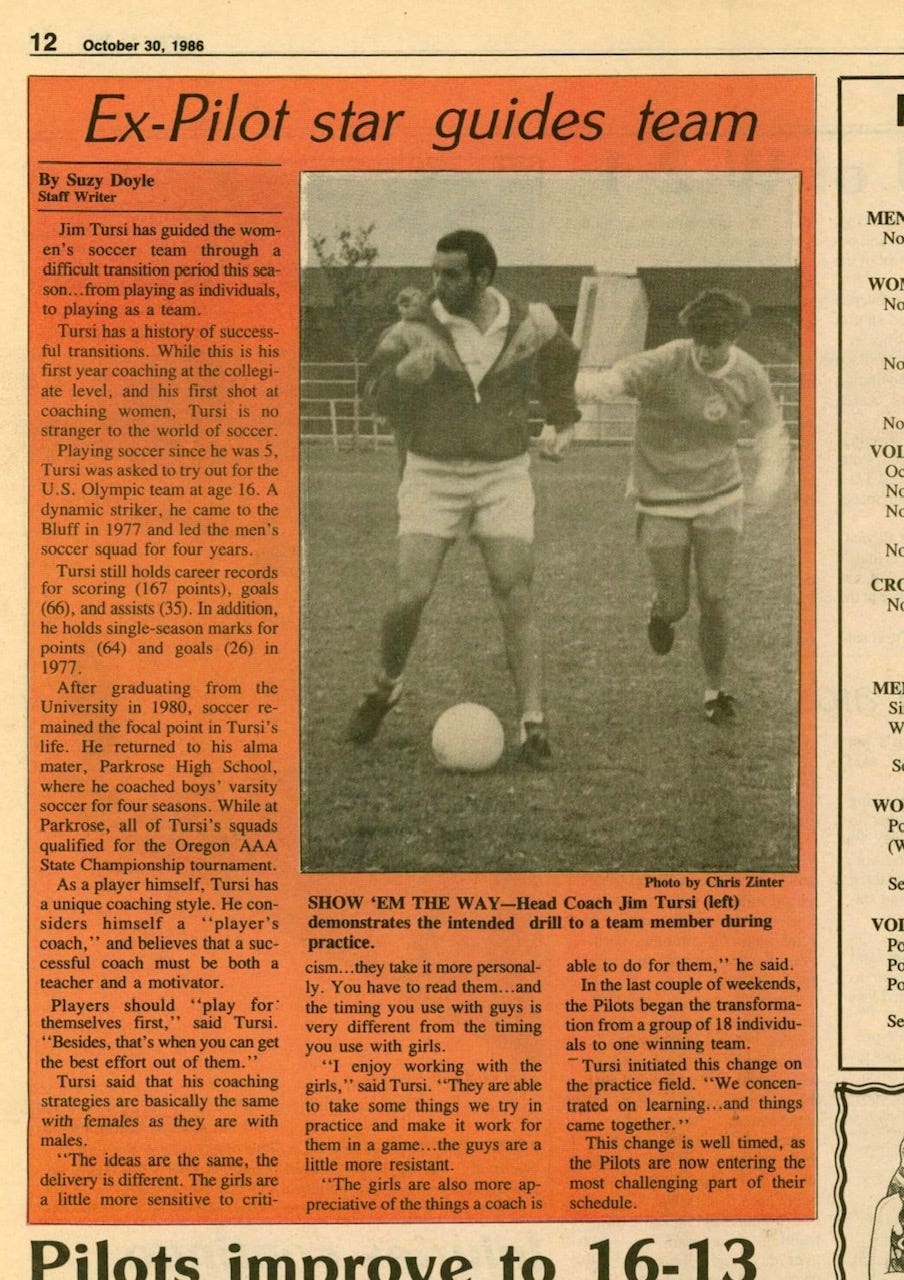

“I”m not a men’s coach or a women’s coach,” Clive Charles told The Oregonian’s John Nolen. “I coach soccer players. I coach one soccer program.” This was one year after Charles took over the women’s program from former Pilot standout Jim Tursi in 1989.

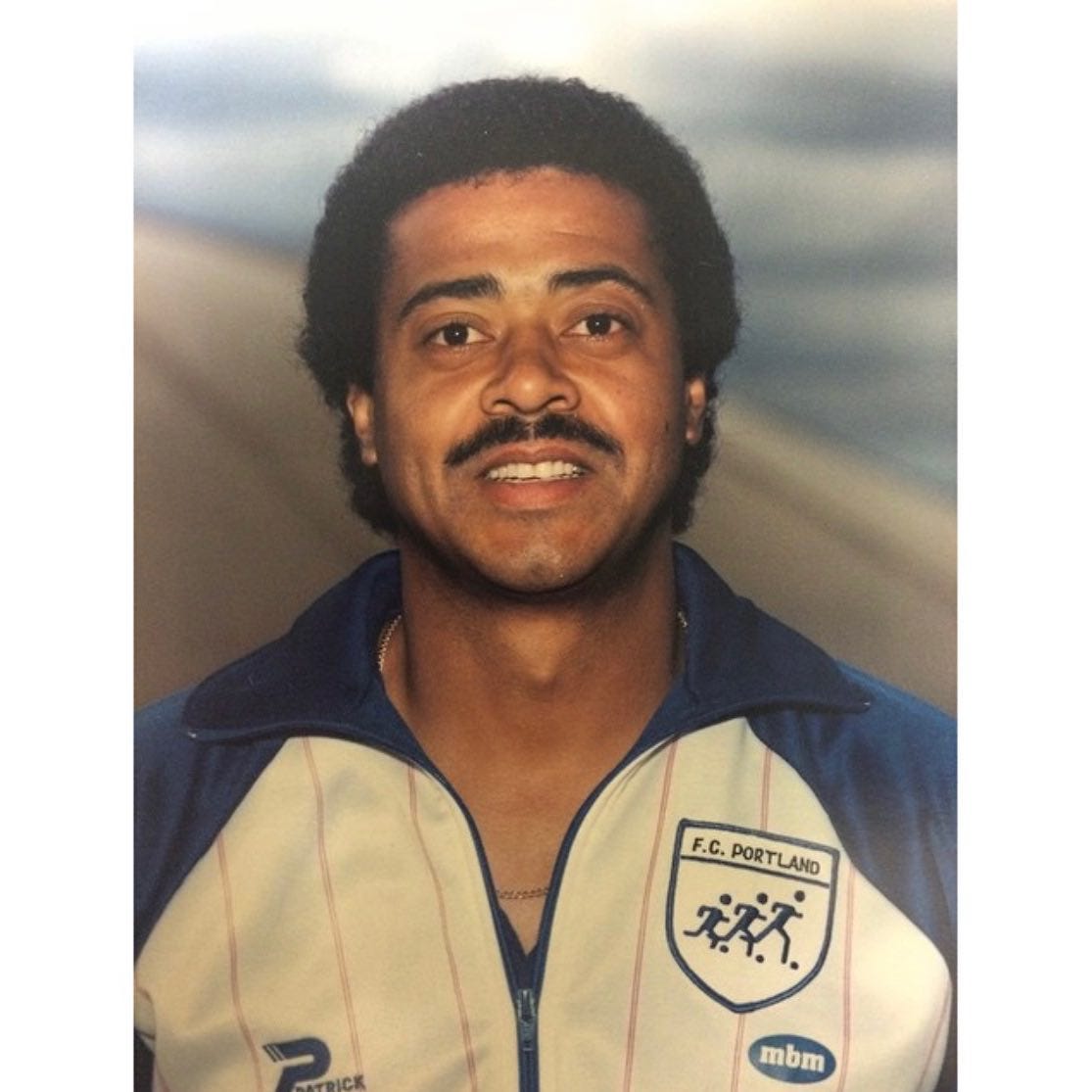

The NASL folded in 1984, with the Timbers stopping operations in ’82. For most of the decade, in the absence of stable leagues, former NASL players found other roles building much of the youth and college game. A few still sought the occasional playing paycheck, but stability was also important.

Jim Tursi first met Clive while playing for the Timbers. “They needed three Americans,” the native Oregonian said of his spot on the team, referring to NASL roster rules. But Tursi never wanted to chase the game much beyond Portland, so he did what many of the others did. “I started coaching, and I fell in love with it.” Tursi started with high school coaching, but took over his alma mater Pilots’s women’s team in 1986, when the university decided to move the women’s program from a club to varsity sport. “I think they gave me three scholarships to work with,” he said of the part-time job.

At the same time, Tursi started Tursi’s Soccer, which is today Oregon’s largest soccer supply store. In 1988, when the store started to take off, Tursi looked at the positions he and Clive had coaching the different programs: “[Clive] was part time, and I was part time.” Jim decided to focus on his burgeoning business, though a few years later he would go back to part-time coaching at Willamette University, leading the Bearcats to two NCAA Division III Final Fours.

So Clive took over the women’s program at UP. “I said I’d do it,” Charles recalled to Brian Belton in East End Heroes, Stateside Kings, “but only if the program was brought up to the same standards as the men.” One step toward that was getting the university to produce one media guide for the program, not separate ones for each team.

Charles’s first recruit was Cindy Griffith, who’d been training at FC Portland Academy. “I had no intention of going to UP,” Griffith said. She was set on warmer, beachier California. “When Clive told me he was going to take over the program, he said we're going to have a new field and all his plans on recruiting some better players, and yada, yada. Right then my dreams of going down and playing at Santa Clara or Santa Barbara went out the window, because I was just so enamored with Clive, I loved him. And so I just set my goal—I'm going to UP.”

Griffith did her due diligence, properly giving closure to her other suitors. “I remember Jerry Smith from Santa Clara saying, ‘OK. I respect that, but if after your freshman year if you don't like it, call me.’” In the third match of the following season, the Pilots beat Santa Clara, 2-1 in overtime. Griffith never called. “[Clive] was a mastermind of the game. He was just brilliant. And then top that off with his charismatic ways and getting the best out of every player, regardless of their skill,” she said. “Clive just out-coached them. It was pretty remarkable.”

“For me, it was because I knew what I was going to get under Clive,” Tiffeny Milbrett said of her decision. “I trusted Clive to the nth degree, and that is critical for me as a person.”

It also helped that standout Griffith stayed in Oregon to play. Milbrett remembers Griffith as “a really solid player” from her FC Portland training who was planning to go to a California school. “I remember she decided to stay [and go to UP]. That was such a big deal to me that Cindy Griffith decided to stay.”

The following year, Milbrett’s first, Clive continued to build both the now-famous facilities and the program. “My freshman year, they were building Merlo,” Milbett said. “So we had to play out at the Tualatin Hills Recreation Center. Wisconsin came in and they were ranked 13th or something which is a big deal, right?” The “home” team won 2-1. But there was also something larger.

“Everything Clive touched, he backed up. Then my freshman year, when we beat that 13th ranked team, it’s like, OK, not that we’ve arrived, but this is all legitimate,” Milbrett said. “And then we got on Merlo Field and just everything seemed more of a legitimate investment.”

Trust and honesty are important when building any relationship, yet alone in coaching young people experiencing independence for the first time. Clive’s ability in these areas far surpassed his already high soccer IQ. “He was very honest with players,” John Bain remembers of coaching with Clive. “You practice how you play, and so he could push people.”

With the connections complete and results following, things progressed, primarily because of everyone’s connection with each other. “Clive didn’t really look at you as a woman or…I mean, he was teaching soccer,” Griffith said. “He had this gift, he respected everyone, regardless of your gender. And he respected your ability to do whatever he could get out of you.”

Tracy Osborn came to the program in the fall of 1991. “That was the first year the women’s team had ever been ranked nationally,” she said. “We didn't make the playoffs that year. But then the second year, we made the playoffs. And then each year we got farther and farther and then my senior year we were in the Final Four that was played at University of Portland.” That four-year period, for Osborn, is what drew her to choose playing with Clive over the usual suspects of national powers. “When I was looking at colleges, I wanted to go somewhere where I felt like I could contribute right away and help build a program. [Santa Clara or North Carolina], they’d already won, right? It was important to me to be somewhere where I could help build something.”

Outward facing aspects matter, as well, especially when competing for highly talented players. This stone didn’t go unturned as Clive built both programs. When it was time for deciding on new sponsors, all players from both teams were consulted before making decisions. “The first year, you know, we had this little teeny locker room, we had these sweats that didn't zip up,” Osborn said. By her senior year, the teams had signed with Adidas. “We had a couple sets of uniforms, new shoes. We felt like professionals by the time we left.”

“Clive was willing to do anything,” Milbrett said. “I learned from him that if you want to be the best, you’re going to have to take on the best.” In 1992, Charles brought in the defending NCAA champion North Carolina Tar Heels, who at that point had won nine of the first ten championships in the sport. “We went down 1-0 within 30 seconds”, Milbrett said of what would end up a 6-1 Tar Heel victory. “That’s what we needed in order to grow,” she said. “I love that Clive was never afraid of a challenge or trying to grow through putting us in situations where we need to play the best to become the best.” Bill Irwin said he and Charles were simply “putting players in situations where they can learn. It’s all about the players and making them better.”

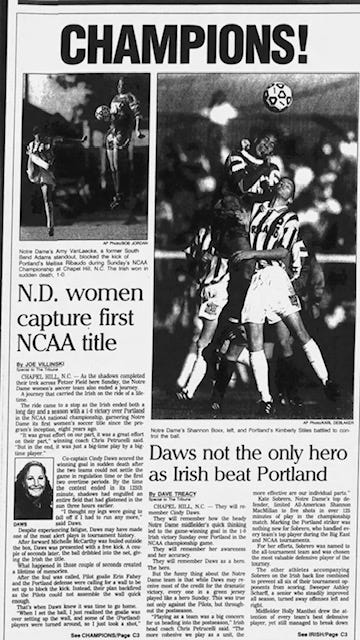

In 1995, for the first time in the fourteen years of the competition, an NCAA final didn’t feature North Carolina. The Pilots met Notre Dame in what would be the longest final in history. It took a third overtime period for Notre Dame to find the golden goal, but the circumstances, and reaction, speak to the character and perspective at the heart of what Clive was really building.

Now-Pilots women’s head coach Michelle French was on the field that day. “There was a foul, and we immediately stepped in front of the ball, because it was definitely within shooting range. The referee turned to us and pointed to his whistle, which generally means ‘on the whistle,’ right?” As the referee is moving the wall back, “they take the shot and score. We're not even thinking that they're going to be able to take the shot because it was going to be on the whistle.”

“The goalkeeper was lining up the wall,” Bill Irwin recalled. “The shooter should not have been allowed to take the kick.” Both Irwin and French remember being frustrated with the way that match ended, and both remember Clive’s reaction. “I took losses more outwardly than he did,” Irwin said. French remembers it vividly:

“We're up in arms going crazy, objecting to everything. And Clive is just as cool as he can be,” she said. “He stands up, goes and shakes [Notre Dame coach] Chris Petrucelli’s hand. Clive was so calm. I don't remember his exact words. But his reaction alone, I think, is very descriptive of the type of demeanor that he could have regardless of the situation and how for him, the game is the game. Sometimes it goes your way, sometimes it doesn't.”

Clive was there to help players find their potential, not his. “When I was playing for West Ham, even at 20 and 21, I was coaching in schools, doing clinics and so on,” Charles said in Belton’s East End Heroes, Stateside Kings. “So it was a long time ago I realized I had something to say, and thought that it was good enough for people to want to listen.”

At that same time, coincidentally, Charles realized something else. While on loan from West Ham to the NASL’s Montreal Olympiques, Clive met his wife, Clarena. The Olympiques’ name also presaged elements of this story. There are the obvious examples, Tiffeny Milbrett’s 68th-minute strike that secured the gold for the US in 1998; the first American goal that match was also netted by a Clive-coached Pilot: Shannon MacMIllan.

There’s the 2000 Sydney Games, where Clive managed the only US men’s team to reach a medal match. “One of the things that I regret not having in my career is a guy who believed in me in my [professional] club soccer, the way that Clive did,” said captain Brian Dunseth. “I always felt empowered when I stepped on the field with him.”

There are the other, lesser-known connections, like the 1980 Moscow Games—where a 16-year-old Jim Tursi worked his way through the player pools to be with the US team before the boycott cut short any chance. “I trained all summer at [Palisades Tahoe],” Tursi said of his work with the Olympic team. He was going between that training and his ODP state team. “I was at the top of my game.” Tursi ended up at UP instead of Moscow, where he still holds the college’s men’s career records for goals and points.

The most unknowingly recognizable connection is from the 1972 Summer Olympics in Germany.

“My dad was in sales presentations at Boeing. So I played with art stuff over the years,” Tote Yamada told me. He recalled back to 1987, before a lot of tools (and regulations) we know now. The FC Portland challenge team had a logo, but the academy got what would be an upgrade, courtesy of inspiration from the Munich Games soccer pictogram. “This predates computers,” Yamada said, “so mostly I had to xerox things, cutting and pasting and gluing.” When he says cutting, he means with scissors, and when he says pasting, he means with glue. “I drew one of those little guys and then ended up just xeroxing and shrinking.” Voila! You have a crest with three players of increasing sizes representing development.

FC Portland started with a challenge team in 1986. At a time when the American soccer landscape was pretty bare. In the 1987 FC Portland Challenge team introduction, Charles wrote, “If we’re going to have great soccer players and teams in the United States, we must first build our soccer tradition from the ground up.” After referencing the European model where local players are developed by their hometown teams, Charles wrote, “FC Portland exists to make soccer strong in Oregon and to build this tradition in the unique American sports environment.”

The FC Portland challenge team gave players a chance to compete against other top players outside of the college environment. “I had a really good freshman year [at UP]” Wade Webber said of his path to playing on the challenge team. “I got on the field as a 19-year-old, playing with men. Guys from Warner Pacific who were a couple years older than me, but also guys who had graduated.” Clive had not yet assumed responsibilities at UP, and it was Webber’s first exposure to the coach. He describes realizing “I don’t know anything about soccer. I thought I knew how to do it, and it turns out, I had no idea.”

“When we started FC Portland, it was an academy,” Brain Gant said. “It wasn't a club. We never had teams.” Yamada echoes the intent: “It was not going to be a club, it was just going to be an academy of training opportunities, where [Clive] would bring players together, they would train and then go back to their other clubs, but he wanted to get some of that foundational knowledge into them at an early age.”

The other lessons were equally important: “If you didn’t show up with the right gear, you didn't train,” Yamada recalls. These are the little things Charles felt important at all levels, and many players know: not being early is being late, show up with clean boots. But also, there’s the larger-picture altruism: In an oral history of Clive the Timbers and Howler produced in 2015, Clarena Charles put it clearly, “At West Ham, the younger apprentices had to clean up after the older players. They had to clean their boots and they had to clean the locker room and they had to clean the bathrooms. [Clive] realized how hard people that the players don’t see have to work to keep the stadium clean, to keep the locker room clean. And so when he started working with the kids, he said it’s not fair to have people picking up after you when you are perfectly capable of doing it yourself. So that’s what started all of that: tuck your shirt in, clean your boots, make sure you have everything. Pick up your tape and your mess off the field. And it was part of a development to complete the person, to think of others, not just yourself.”

What most impressed Yamada within this system was Clive’s ability to scale one skill across all ages, and to communicate that to the often younger coaches running the sessions. “He’d bring each coach a sheet of paper and say, ‘here's what we’re going to do’ and everybody was running the same drill, from the U10s to the U19s. And the kids would get the concepts, and they’d just be doing it at a little bit slower pace, or a little bit bigger grid than the 19s.” From there, Charles or other coaches would move players around within the session to put them in the best place individually.

“Development. That was his goal,” Clarena Charles said to Brian Costello and Leander Schaerlaeckens. “That was what he wanted. He wanted to make soccer better in Portland, in Oregon, in the US, and have them be able to compete at each level nationally or internationally.”

One player that embodies the success of that model is Chris Brown. The Oregon native has won the top prize at nearly every level he’s played: Four high school state championships bookended by an MLS Cup with Kansas City. Brown came of age when FC Portland Academy was just becoming a club. Brown, like many players, first met Charles through ODP, but as Clive was also starting the club. The challenge was that the first team would be U17, and Brown was a few years younger. “There were a couple other guys, like Andrew Gregor and Mike Holloway [who were younger]” that joined the U17s. That core eventually played their own age as the club grew into formal competitions, eventually winning US Youth Soccer’s national championship in 1994. Their coach at FC Portland was Jim Rilatt, who also coached the Timbers U23 team to an undefeated season and USL Premier Development League national championship in 2010. The foundations, Brown said, were all about “being a professional, being an adult.’ “The thing that gets lost a little bit in the soccer,” Brown said, “is that Jim and Clive set up FC Portland, but it wasn't just soccer. They were teaching us how to be good people, how to be a professional.”

The days training with FC Portland, and later UP, taught Brown how to play more than one position, to understand the game. “To be honest,” he said, “I made a 10-year career of being able to play everywhere.” But technical ability is only part of the equation. “What I learned from Clive that carries with me in my personal life is a sense of a holistic understanding of everything around, even parenting, definitely coaching. Because I think a lot of the way I coach in life, I model in some form or fashion after Clive.”

Though I was able to play with FC Portland when I was younger, my biggest honor was getting a chance to coach with the club. As both a player and coach, I’ve always preferred training to games because that’s the hard place to really test oneself and learn. As a player, it was a chance to work, to make mistakes, to get better. As a coach, training is a place to push, and teach, and bond, and learn from the players. The matches themselves are for the players.

When I first started coaching with FC Portland, I remember a session a fellow coach, Brandon McNeil, was setting up. It was a vintage Clive-Charles early-season special: one-v-ones. As Brandon set up the grid, I questioned its width. “I don’t know,” he said. “That’s how Clive set it up, so… .” He smiled at me and kept on laying cones.

The training ground is a place of great trust. It reveals as much about players as it does coaches. Wade Webber became a believer of training when under Clive. “I was used to the game being the most important thing, that you play the game, and then you’d get through whatever practice was, you know, whatever. It’s not like you're learning anything at practice,” Webber said of his pre-Clive attitude. “And then suddenly, with Clive, he revealed things, subtle things like body shape, angles.” Webber knew communication was key for his position, but he didn’t know how to do it. “No one ever told me what I was supposed to say to these people,” he said of being on the field, “So I was Shakespeare on the fields, giving these long-winded things.” Clive told him he had to rely on more effective communication: urgency, specifics, and, of course, “a reduced number of syllables.”

But Webber, MLSNEXT PRO Tacoma Defiance head coach, also learned from Charles the art of trying new things. And knowing when they don’t work.

“Clive would come to training sometimes with a napkin in his hand,” Webber said. “He’d say this idea came to him for this new exercise, the way to train something. And this one day, he has the goals facing each other quite close, like 10 yards apart. He’s got this idea: it’s teaching defensive heading, how to be aggressive, attack the ball at its highest point and head up, heading upward to clear the ball out of danger.” Webber talked about how the first two up were Gary Osterhage and another player. “And you could probably see the potential flaw in this plan, right? The first ball he throws up,” Webber said, “the very first one, Gary and Paul climb up and smash heads.”

“I had to go to the emergency room and get stitches that day,” Osterhage said.

“[Clive] crumbles that piece of paper and chucks it and says, ‘Well, we’re not doing anything like that,’” Webber added.

Ultimately, however, it always came down to the things Tiffeny Milbrett said in her hall-of-fame speech: vision, kindness, care, and love.

Training sessions were simple and focused, and the expectations of players stepping over the line onto the field were clear and high, but the effort was worth the yield. To this day, Clive’s players remember the simple, important things. From Cindy Griffith: “He taught me how to defend correctly. He thought it was important that every player, regardless of position, needed to know how to defend”. To Scott Sagar: “The greatest thing that Clive gave me was for me to open my eyes, and recognize the flow of the game, and recognize what I could do for the game based on what other players might be doing. To Kasey Keller, who talked about how Clive would treat the twenty-second player on the roster the same way he’d treat the star: “I think everybody that played for Clive realized that they were a better person for spending that time with him; not a better player, not a better student, but an overall better member of society”.

Sometimes this extended to saving players from unfortunate hairstyle choices, like the time Chris Brown showed up to training with blonde hair and Clive told him, “Don’t step back out on the practice field until you change your hair color back.” And there’s the gentle nudge to Tote Yamada. “I had a mullet halfway down my back,” Yamada said. “[Clive] came to me and said, ‘I'm not going to tell you to cut your hair. And if you need me to go to war with [Pilots AD] Joe Etzel, I will do it, but it would help me greatly if you would cut your hair a bit.’” Yamada respected Charles so much. “If somebody else said ‘cut your hair,’ the rebel in me would have said, ‘No way.’” There was only one logical resolution, however: “I cut it that day.”

And sometimes, it’s about more than the mullet. Success, Wade Webber said, was “a result of two years of Clive breaking us down and building us up. I had a mullet,” Webber admitted. “I didn't wear shin guards.” It’s a not-uncommon youthful confidence that comes with the age. “When Clive was trying to get me to play the way he wanted me to play central defender, I didn't look like a good player. I struggled to do some of the things that he wanted me to do, while still doing the things I wanted to do.” Charles would give Webber a hard time about his hair, but “he never made me cut my hair. I would just cut the sides even shorter.” On Webber’s 21st birthday, he took a visit to a local barber. “We called him ‘Jimmy the Hack,’ Webber said. He paid his $5, “and got an adult haircut, a proper haircut. The next time I saw Clive, he just had a little grin.”

But that was just the first step. “The very first day of pre-season, we went into those one-v-one boxes, and that was the day it all changed, that training session,” Webber recalled. “I was the first guy in the box and I'm tired. I knew that he'd brought in this recruit from Canada for the next year.” This was the spring pre-season. Webber’s soon-to-be-center-back partner on that ’88 team, Ian McLean, had signed on, as Clive told Wade, “to either take [his] job or play with [him]. One of the two, we’re either going to be both the center backs or it's going to be him and Trent Schultz, the younger guy.” Webber continues, “In that grid, the ball gets knocked out at the end of it and, and instead of getting my one round of rest, Robb Sakamoto ran after the ball, like he's gonna turn and bring it back into the grid and go at me again. And I saw red, the mist descended, and I chased him because he was chasing the ball. And he turned with it and I’m in the air and launched two-footed into him.”

Webber still feels bad about the tackle. But he also sees the significance. “Clive, the minute I did that, had a great big smile on his face and said ‘We’re done here.’ And we went in, that was the end of training. We trained for about 10 minutes. That whole thing was geared around getting me to play the way he wanted me to play.” Webber said of the short session. “I wouldn't have had a pro career if it wasn't for Clive. From that moment on, I defended one way,” a way that anyone who knew him prior wouldn’t recognize. “And that’s one example of Clive playing the long game. He kept on me, and eventually it had to be my decision.”

Even as Clive coached throughout the US Soccer system, he modeled the respect he expected from his players, and this left an impact on his future Olympic captain Brain Dunseth. While training with a US Youth National Team, Dunseth remembers spotting Charles on the sideline: “You see this guy who’s in US National Team gear kind of sitting there on the sidelines, and you’re like, that’s Clive” Dunesth said of his first encounter. ”We already heard whispers that he was going to be the Olympic coach. I just remember sitting on the sidelines, while everyone was wrapping up practice and him not wanting to interfere with [Youth National coach] Jay Hoffman” who was running the session. But afterward, Charles and Dunseth had a brief conversation. Charles told Dunseth he liked the way he played, and that he was in contention for the Olympic team. “It was a quick little conversation, but it was enough: OK, cool. He believes.”

When the two worked together, Dunseth saw the strengths Charles brought to the tactical side of preparation. As they traveled in preparation for the Olympics, Charles taught Dunseth and the team the value of diamonds in formations and adjustments. “It's the perfect formation in my eyes,” Dunseth said, “because you can play any team [in any formation] and it doesn’t matter; you’re always numbers up in the midfield, because you always have those four guys and an outside back.” Like at UP, Charles’s players knew the system so well they felt not only empowered to adjust as they saw what other teams were doing but also to teach each other as new players came into the fold. In an age before YouTube or other advanced technological scouting that can happen at the individual level when players are spending most of their time with club teams, in-person communication had to carry the message, and that happened at limited training. Dunseth described the training sessions as “fun, competitive and tactical. Without standing around and just talking about tactics. There was always a simplicity in his delivery, even though the context was maybe difficult to understand or convey. He just knew how to explain what he was looking for.”

“There is one drill I can remember,” Dunseth says of a session designed to help defenders with sending attacking players a specific way. It was “the simplest drill, but the context of it was he was making you think” about all of the possible scenarios as the play is developing. “I'm thinking about all these things–the attacking player’s preferred foot, center of gravity, pace–and then I've got Clive [acting as a supporting player] shouting at me, ‘I’m on your right’ or ‘I’m on your left,’ and then I’m having to adjust everything that I've just been thinking about to compensate for a teammate trying to double down. It’s that simple drill, probably a 10- to 15-minute drill in a random training session in Spain, and here it’s locked into my head 22 years later.”

That Olympics also stuck with Jeff Agoos. There’s a picture of Agoos from November 2003, just after he’d won his fifth MLS Cup, and he’s on the field in a shirt that reads, “We miss you, Clive.” It was just three months after Clive’s passing. “I've got that [picture] on a wall,” Agoos told me. “I'm looking at it right now. It reminds me every day about who I should be, and about what this game is and what people should be.” Agoos had a playing career that includes making two World Cup rosters and a National Hall of Fame induction. When he looks back at that moment after winning his fifth MLS title Agoos recalls the emotion. “We just lost this effervescent, iconic person that I don't think people got a chance to know well enough,” he says of Charles. “He would have done [even more] great things with the game. But really, more importantly, it’s the people he touched in his career.” Agoos reminisced about some of the lessons Clive left in his legacy. “It’s what he put on the line every single day: Can you be a better person? Can you be better than you are today? Can you be a better teammate? How are you going to make somebody else’s life better?”

“I’ll never forget the Olympics,” Agoos said. “It was one of the highlights of my career.” Charles chose Agoos as one of the three allowed over-age players to join the team—an atypical pick to take a defender. But Agoos’s World Cup experience made him a likely leader. Yet, the younger Dunseth retained his captaincy as the roster developed. “This is another reason I give Clive such a great amount of respect,” Agoos said. “He could have made any of the overage players the captain, but to do so would have undermined the players who qualified that team.” Keeping Dunseth as captain “showed that there was a level of respect for the players who got [the team] there.”

The FC Portland club philosophy starts with these words: “Clive Charles founded F.C. Portland Academy in 1987 with the key philosophy that: ‘Through the game of soccer there is an opportunity to prepare and develop young people for the challenges of life.’ The Academy continues striving to uphold Clive’s vision for soccer and player development both on and off the field.”

We’re all in this together, and Clive seemed to see that. Gary Osterhage’s Civic Stadium goal in 1987 came just one day after the ninety-fourth anniversary of the first ever Association Football match in Portland, when, in the nearly the same location in downtown Portland, on October 21, 1893, the Portland team beat the Astoria Football Association, 5-0. Gary’s was far from the first goal on that location, and not even the first goal of that match, but it was a trajectory changer, for UP, for soccer in Portland, in Oregon, in the US–because it enabled Clive to build through his unique vision.

“Clive told me once that your first coach is always the coach you are locked into,” Jim Riltt said. “You’ll meet other good coaches along the way, but it's almost like they'll never top your first coach. And I think for a lot of people that played for Clive, that rang true. He helped so many people in so many ways, guiding them through their young adulthood.”

“With Clive the individual was always first,” Kasey Keller said. “If we keep the individual right, everything else will fall into place.” Clive invested. He understood individuals and that, as Keller put it, “there are different ways to treat different people depending on their personalities, where they come from, and how they’re moving forward. It was an extremely unique insight that he had and a major reason why he was so well liked across the board regardless if you were playing or not.”

Justi Baumgardt was a three-time All-American at UP. She married Tote Yamada, who shared a story about when Baumgardt was working on free kicks outside of training. Clive was there waiting to meet a male recruit. “The recruit comes up, and Clive tells him, ‘that’s the best left foot that’s ever walked on this campus,’ and Justi pings a ball into the goal,” Yamada said. Then Clive and the recruit start to walk away, and Charles adds, “Other than mine.”

“Clive had the success he had as a player, he was thankful for the game, and the opportunity afforded him and so for him,” Shannon MacMillan said. “It was about giving back to the game, and how he could make a difference. It's something that I think about all the time: how would Clive treat this person, how would Clive do it?” MacMillan was touched to know “someone that just truly cared so deeply about his players, about the teams, about the program.”

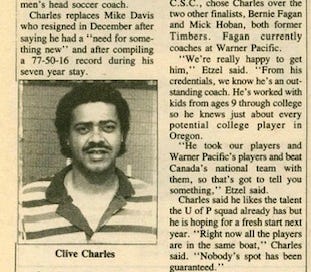

When Clive Charles was hired by the University of Portland in 1986, his pre-season quote in the school’s newspaper, The Beacon, had him saying this: “We have the ability to be national champions.” He continued, “Every season that I’m here, we will shoot for that goal.”

He believed. In people. In building something lasting. In giving back. From Day 1 in 1986.

On December 8, 2002, just before the NCAA championship match, Clive gave his Pilots these important instructions: “If you have fun, you will win.” And then he uncharacteristically inserted himself, “and you will make me very, very happy.”

In the second overtime of a rain-soaked Austin afternoon, with the Pilots and Santa Clara Broncos tied 1-1, just under seven minutes from penalties, a Kristen Moore cross found a sliding Christine Sinclair, whose initial shot hit off the goalkeeper and then post before Sinclair, who is now the world’s leading international goal scorer, sprang on her own rebound and finished what has to be one of her personally most rewarding goals.

It was a simple right-footed finish off the laces, the golden goal, the first national championship for Portland.

It was the last ball kicked in a match Clive coached.

[The above quote links to the University of Portland Pilots video about that match]