This Cascadian Life (April 2023)

A beautiful thing about soccer is that it allows one person to make thousands of other people feel what they are feeling, the exact same emotion, at the exact same time—almost as if, in that moment, they all share the same brain. The same heart.

Take the 71st minute of this month's Timbers/Sounders Cascadia derby, for example. With a ball coming toward him in the air, Portland’s Dairon Asprilla leapt, back to goal, and connected, sending the ball past Seattle 'keeper Stefan Frei to tie the match at one goal each.

And in that moment, Asprilla’s inspiration turned to everyone’s amazement, everyone’s joy, and a celebration of what a human could do, what he did do.

“Today was a big day for the fans,” Asprilla said in the post-game press conference. “I stay ready every time for a bicycle,” he explained. “I love this. When I saw the ball, it was perfect for me, and I tried.” Asprilla then put showing up for the moment in the perfect context: “When you have a dream, you try, every time.”

When we come to the field, when we bring our dreams, one moment can, and does, make us all feel something lasting. Together. That’s the irreplaceable thing about soccer, about sport.

Portland added a Nathan Fogaça goal 5 minutes after Apsrilla’s stunning shot, then needed just 5 more for Jarosɫaw Niezgoda to tap in, and then 8 more for a Juan Mosquera add-on, turning a one-goal deficit into a 4-1 lead in 18 minutes against the MLS Western Conference points leaders and Cascadia rival Sounders. Though it’s too soon to tell if the goal could turn the season for either team, those who witnessed the 30-year-old Colombian’s bicycle kick were privy to what’s pure and beautiful about soccer.

In this month’s Green is the Color, stories of what happens when we put the world’s game into one bioregion, mix it for 50 years, and regularly come together for an unpredictable 90 minutes of celebration.

That’s coming up, in “This Cascadian Life.”

Act 1: “And That’s What Happened”

You just never know what you’ll find when you show up to the stadium. But for those who are game, there’s always something special.

For Scot Thompson, his first time there is still one of his two favorite moments with the Timbers, and it came before he’d even slipped on the number-17 jersey he’d wear to the then-all-time Timbers’ record for minutes played. After finding out he’d been loaned to Portland from MLS side Los Angeles Galaxy, Thompson did what any 23-year-old in 2004 would do: He road-tripped.

“When [the Galaxy] told me that I was getting loaned up here,” he remembered of his first time to Portland, “I just grabbed my stuff and jumped in the car.” Fifteen hours of driving later, Thompson’s welcome to Oregon was seeing a man up on a snag wielding a chainsaw—at a soccer game, in the middle of the city. “I made it right to [PGE Park at] kick off and seeing Timber Jim climb that pole, banging his drum….” Thompson arrived knowing nothing of the team, but “that was a pretty cool moment. This is a pretty cool setup,” he recalled thinking. “There’s something special here.” 156 appearances later, One-T, as he’s known in Timbers’ lore, showed up and found out, from Day 1.

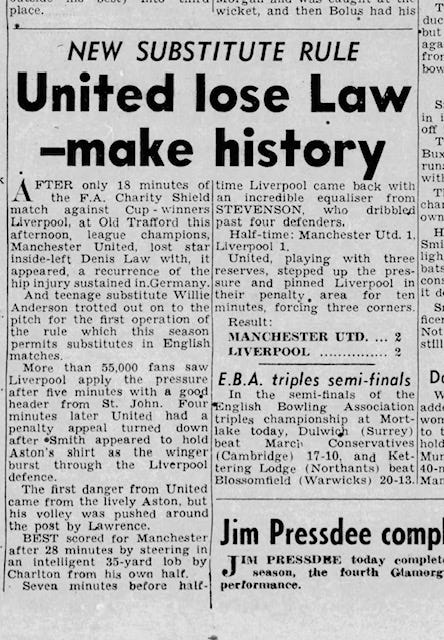

Nearly 50 years earlier, 18-year-old Manchester United’s Willie Anderson received a telegram at his Liverpool home, calling him into the 1965 Charity Shield with short notice. “We didn't have a phone in those days,” he remembered. “And the telegram says something like, ‘You’re in the first team squad. Be at Old Trafford tomorrow at noon.’”

For Anderson, the call-up was amazing on two fronts: he’d get a crack at first-team football, and he’d play against Liverpool, the hometown team he grew up watching, “It was such a huge thrill to run out there and play against guys I was cheering on a couple of years before,” Anderson reminisced. “Yeah, that was really fun.”

That next day, in the 18th minute of the match, Anderson came on in place of Denis Law, becoming the first substitute Manchester United ever used.

The substitute rule was so new, the English league hadn’t yet decided if the one-allowed sub would be given a blank-backed shirt or the number 12 which would signify a reserve. In that match, Anderson entered numberless.

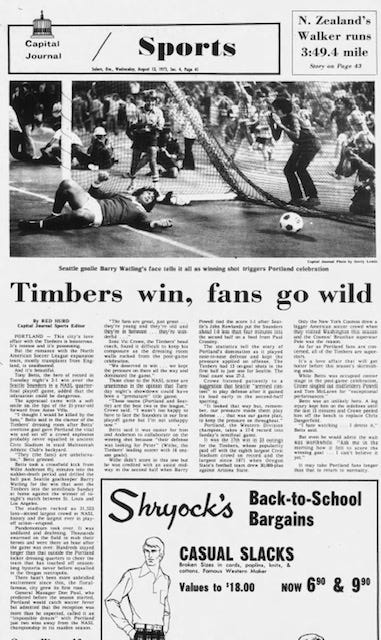

A short 10 years later, Anderson found himself with a new team for the first time. After playing a May 12 Welsh Cup Final for Cardiff City FC, he traveled 4,600 miles to join the NASL’s Portland Timbers. The team had already played thrice by the time he arrived in Portland. “I flew in on a Wednesday night. They gave me Thursday off to recover,” he said. “And they came in on Thursday and said, ‘Hey, you know, you feel ready to play? Because we fly out tomorrow to Vancouver.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, sure, I’m ready to play.’”

But upon entering Vancouver’s away-team locker room at Empire Stadium, his emotions momentarily changed. “They gave me my uniform, and it said number 12,” Anderson recalled. “And I kind of lost it, saying something like, ‘I didn't come all the way to bloody America to be a sub.’”

But the new Timber was quickly calmed with an explanation and introduction to how things are just a little different in American soccer. “No, no, that’s your shirt for the season,” Anderson remembered the team telling him.

That seemed to do the trick. Willie Anderson started, and it took him all of 9 minutes to register his first assist—on the first-ever Timbers’ Cascadia goal—when he set up teammate Barry Powell. “I remember I got a ball in the box,” Anderson said of that match. “And I backheeled it to Barry, and he just whacked it in.” (Anderson, in the number 12, would go on to tally 53 total assists, putting him just 2 behind John Bain’s NASL-Timbers’ best 55.)

Six minutes after that, Timbers original Tony Betts registered his first-ever goal in the green and gold—”I think it was a pretty easy one, if I remember rightly,” he said of his 15th-minute close-range header—sealing the 2-0 Timbers win over the Whitecaps.

Forty-eight years forward to this month, 2023 Portland’s Franck Boli made an Andersonesque contribution in 4 fewer minutes. Away to FC Dallas, newly acquired Boli knew he would possibly get a few minutes. “It was fun to watch, as I was sitting on the bench,” Boli said of the April 1 draw in Dallas. “The [Timbers] started well. The team was very good.” The Ivorian got a chance to leave his own mark. “I came [into the match] to participate, and I’m thankful for the coach to give me 5 minutes.”

Boli equalized in the 90th minute, one-touching a Dairon Asprilla pass into the net. “It was very brilliant from [Asprilla],” Boli said of his teammate's assist. “What a great start for Boli,” Coach Savarese added of the 90th-minute equalizer. “There’s a good feeling around the team that we started to move forward.”

That’s the power of a goal. It moves the players, it moves the fans. It provides the ultimate release of emotion.

John Bain is the Timbers’ NASL leaders in goals and assists. When I asked him which he prefers, he didn’t hesitate. “Scoring goals,” he said. “Scoring goals, without a doubt. There’s no question.”

I followed up, asking what it’s like to score a professional goal. Bain was simple and perfect: “It’s a good feeling,” he said. “I loved to play, and I just loved scoring goals.”

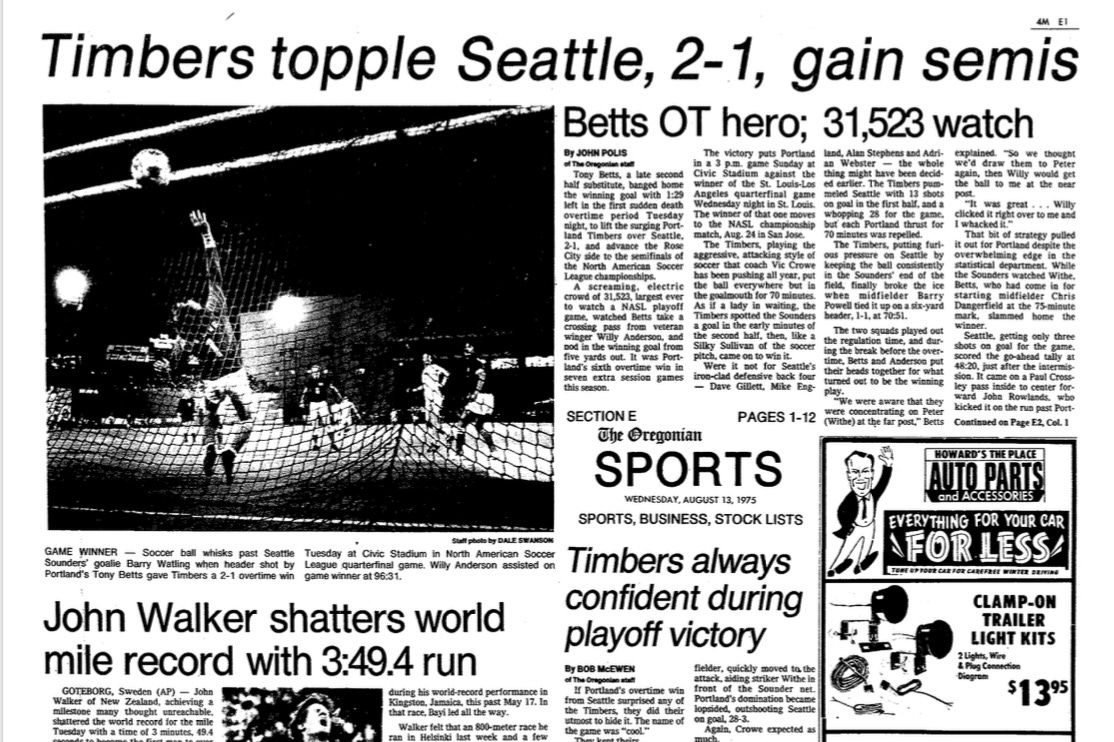

To the same question, Tony Betts concurred. “To score goals is the best thing,” he said. “Even when I was a kid in grammar school, and with the youth team at Aston Villa when we won the FA Youth Cup…. Scoring goals, no matter where you are, whether it’s in front of 70,000 people or 7, it is a very thrilling thing.” And for Betts and many from Portland, it never gets better than one he scored in front of 31,523 at Civic Stadium.

He wasn’t supposed to play the 1975 NASL quarterfinal match on August 12. He’d been injured a game prior and was dealing with a pulled quadricep. As the match went on, Betts got a chance. He recalled coach Vic Crowe’s substitution instructions. “‘Tony, just go on there and try to score a goal.’ And that’s what happened.”

“Yes, I’ll never forget that [goal],” Willie Anderson said. “It was a huge night; we had 30-odd thousand out there or something.” He talked about how big the matchup with Seattle was for the fans. “As we found out, you know, everybody in Portland hated Seattle and wanted to beat Seattle in anything. We [players] just got lumped in there.” That added perspective.”The fans were so crazy because of their dislike of Seattle. And they just brought it with them.”

After 90 minutes, the match was level at 1 goal each, so they went to sudden-death overtime. About 6 minutes into that, there came a chance. “I always preferred crosses to come in from the right wing,” Betts said. “I wasn't brilliant with crosses coming in from the left wing.” But that’s where the ball was.

“It was a corner, it went out to Jimmy Kelly,” Anderson remembered. “And we were both on the left side. And he just put me in behind everybody. It was a great ball from Jimmy. I caught it great with my left foot, and bingo—it just landed on Tony’s head.”

“When Willie crossed me the ball,” Betts said, “it was just, Okay, go head it.”

And that’s what happened.

“The beauty of it was, as soon as [Tony] scored that goal, the game finished,” Anderson said of the sudden-death goal. “Pandemonium broke out and the crowd flooded the field. It was a huge, huge night.”

Indeed it was, for everyone who showed up and has been showing up to 1844 SW Morrison Street every night since.

Act 2: The Opposite of Love Is Love

Brian Gant told me a story from when he was a Timber, the kind that could have taken place at any point in the past 50 years in this region—the type of allegorical anecdote where you could change any name of any player or coach, or insert Seattle or Vancouver or Portland, and you’d get the same moral.

“We played at Civic Stadium, and the visiting team would come down that roadway under the MAC Club terrace,” Gant, who played for the Timbers 1977-82, recalled about how the bus for Seattle (or Vancouver or any opponent) would stop at the top and let the players walk down to the field, much as they do now.

“It was usually about an hour and a half before game time, and all the teams would sort of gather on the field. And I remember one time, Vic Crowe, oh my god, he came out and saw us out there, just shaking hands.” Gant and most of the players on each side knew each other. “And we're shaking hands and talking and everything. And so Vic, you could just see that Vic was pissed. And so at halftime, we were losing, and Vic came in and absolutely reamed us. And he picked out players he said, ‘If I ever see somebody shaking hands and hugging a Seattle player before a game, you'll never get on the field, I'll never play you…. He just ripped into the whole team, and maybe rightfully so.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

After this month’s first 2023 Portland/Seattle Derby, in the post-match press conference, Sounders coach Brian Schmetzer, who first played for Seattle in 1980, channeled his inner Crowe. “I don’t feel that it’s a rivalry,” Schmetzer said about the game. “After the game, people talking, laughing. It’s not another loss, it’s against the Timbers. All of us have to get back to understanding that this is a rivalry.” He later added, in another question, “This team is a super talented team, and we’re not going to win every game that we play this year, but we certainly are going to change the way that we play next time we play Portland.”

That next time is June 3 at Seattle.

Fifty years of familiarity can breed a lot of contempt. But it’s more complicated than that. There’s so much of the same shared history in this region, over a similar timeline, that it can be hard outside an actual match to separate oneself from one’s purported enemies. It’s further complicated when those lines blur. Ultimately, we have more in common than we don’t, and the game itself becomes bigger than any of us. And from there, we can see an evolution to be proud of.

It’s hard to get more Portland Professional Soccer than John Bain. The Scottish-born midfielder is in the Timbers Ring of Honor and has represented the Rose City playing professionally in an impressive three different decades, from 1978 to 1994 where his playing career ended with indoor soccer’s Portland Pride.

But…he also played for Seattle. “When the Timbers folded [in 1982], I had an opportunity to go to either Seattle, Vancouver, or San Diego. And I chose Seattle.” Bain played that season with current Sounders coach Brian Smetzer, and that Sounders team played the only other Cascadia team operating at the time: the Whitecaps. During that season, the two teams opened BC Place in front of a then-Canadian-record 60,000 fans.

And of the early NASL Cascadia days, Bain credits Vancouver fans for knowing the game, “because they were a little more European-based.” He continued, “when Vancouver came [to Portland], it was one of the few times you could really hear the away fans because fans didn't travel like they do now.”

Canadian Brian Gant’s first three seasons in the NASL were with the Whitecaps, and he echoed Bain’s assessment, adding that the Vancouver fans knew a lot, but also engaged in the game in discussion with each other, not as much toward the game. Yet the Seattle fans, he said, had a different excitement. “They played in Memorial Stadium, and it was really tight, probably 15-16 thousand. They were close to the field, and they’d just go crazy.” Gant even recalled a moment when a Whitecap teammate was punched on his way back to the field after halftime. “When I came to Portland in '77,” Gant recalled of his move to play for the Timbers, “they were like that, too. They were loud and they cheered everything. It was fun. Whenever we played [in Portland], it was like having an extra player.”

But many of the players I interviewed in this piece noted, as did Gant, that the enthusiasm in those early days was for the event more than the nuances of the sport. “They just wanted the team to win, but they didn't understand it,” he said. “It’s not like today. When you go to a Timbers’ game today, there are so many knowledgeable people in the stands, a lot of them played in college or high school, and they know a skilled, organized team from a non-skilled or non-organized team. We never had that. We never had that [in the '70s] at all.”

There just wasn’t much soccer here in the 70s. But guys came here and played and built excitement. When leagues dried up in the early '80s, many of them (who were “lumped in” the rivalry) stayed and built the game coaching. That’s when we had a first generation of American kids who grew up knowing the sport. Fast forward to now, and those '70s, '80s, and '90s kids who have spent their whole life with the game here—because of the NASL players—are starting families of their own, a second consecutive generation who doesn’t know the country without soccer or without the Cascadia rivalry.

One of those players who embodies this is Andrew Gregor, who, like the Timbers, came onto this earth in 1975. The recently named director of scouting for MLS’s Minnesota United FC, Portland native Gregor grew up playing club and college soccer for former Timbers Tony Betts and Clive Charles.

Over his 11-year career, Gregor is also one of the only people to play for all 3 Cascadia teams.

“What made [the rivalry] really unique back then,” Gregor recalled of his time before any of the teams were in MLS, “was the nature of that competition, because you had guys on the teams from the areas they represented. A good chunk of guys on Portland, were from Portland, a good chunk of guys on Seattle were from Seattle, and a good chunk of guys on Vancouver were from Vancouver.” That hometown affiliation made it matter differently for the players. “We all knew each other, grew up playing against each other in different youth competitions or college, so those games were really important on the schedule—just the wanting to have your city and regional pride to want to beat those guys. Because we all had roots in the area.”

When the Timbers played their first 2023 US Open Cup match this month, hosting Orange County SC, a Portland-area product returned. In the 78th minute, Camas native Brent Richards, who was the Timbers’ first-ever homegrown signing, brought a Northwest career momentarily home when he checked in as a visitor in the place where first became a professional.

But in the larger arc, things came full circle in the stands. “I got almost emotional the other day watching [that US Open Cup match],” Brian Gant told me. “Blanco was going off at 30 minutes or so, which you understand—he’s just out there getting his legs under him and everything.” Gant continued, “And everybody's standing up and cheering and clapping. They're going ‘Blanco, Blanco,’ and I'm like, that is just brilliant. That is what soccer is all about.”

Gant’s reaction tells me everything I need to know about where we are. A Cascadia veteran of both the Whitecaps and Timbers, taking absolute pride in the fans and how they support their team and the game. And I hope he knows it’s a moment of passion and knowledge he and so many others helped build.

As for the rivalry, in Seattle, they get it, too. Sounders GK coach Tom Dutra—who, like Sounders head coach Brian Schmetzer, is a Seattle-area native and longtime Sounder—shared a few of his favorite Cascadia derby memories from over the years. But he kept coming back to one thing. “You know,” Dutra paused after listing off a dozen or so great memories of these matchups, finally finding a thread, “the fans. The fans are the ones that make it big, not the players on the field and everything else. I mean, we create the drama in the theater, but it’s the fans. You feel it and you sense it.” The Sounders have won just about every trophy a MLS club can, but the Cascadia Cup is different. “We know this trophy is for the fans. So that's the reason why we want to win. More than any other game. This is about the fans.”

Portland might retain the Cascadia Cup this year. Or, it could go to Seattle or Vancouver. And then the next year and the next, these seasons with the Cascadia Cup provide a competition within a competition. It’s a beautiful cycle that gives each team and their fans—their communities—a shot at temporary regional supremacy and bragging rights.

But for those Portland fans who just don’t want to give anything up to either of the neighbors up north, here’s something neither of them can take away.

On July 28, 2002, Andrew Gregor scored a goal.

“It was on a counter,” Gregor remembers. “The ball got crossed to the near post.” Gregor beat a Whitecaps defender and goalie to the ball. “I just jumped through and flicked it on at the near post and beat the goalie. It wasn’t spectacular or anything, but it was important.”

It was the first Sounders goal scored at [what was then called] Qwest Field, which means it was a Portland guy who scored the first-ever Sounders goal on their current field, and against the Whitecaps. Crown him.

Act 3: It Takes a Village

It’s well after 11 on the Friday night before the first Timbers/Sounders match of the season, and, at 48, I’m probably too old to be standing in the back of a converted 1990 P30 step van with another friend (also a dad from the suburbs) and others, driving nearly 3,000 square feet of painted canvas from a warehouse in Southwest Portland the block and a half it needs to travel to Providence Park. We still have a good hour of work at the stadium, and I still have to drive us dads home after, only to wake on short sleep and get my son to a fishing derby by a little after 7 the next morning. With his youth soccer game immediately following that and then back to SW Portland for the Timbers/Sounders that night, being out this late makes for a long weekend. I’m old enough to know better.

Scratch that. I’m old enough to know exactly what I’m doing, and it’s 100% the place I should be and the time I should be there. Though I don’t know all of their names, nobody in this group is a stranger, and in this van is precisely where any of us belong. We have a tifo to raise—twice that night to make sure it’s absolutely ready for the next evening’s match. After that practice, we’ll put it away where it will sit the next 19 hours until the end of the anthem, when the Timbers and Sounders are lined up for North America’s greatest soccer rivalry.

I’m in good hands. We’re with the Timbers Army, on the field at Providence Park, in the middle of the city, into the late of the night.

The Timbers Army (TA) has long involved any and all comers. “If you want to be Timbers Army then you already are,” is something often shared from the 107IST (107 Independent Supporters Trust), an organization that includes the Rose City Riveters and TA. I joined just this year, in part for this project, to see how the country’s best supporters group functions. Of the many ways to get involved with the 107IST, one is signing up to paint tifo. I registered for my 10-year-old son and me to help with the opening-match tifo (see “No Pity Land (March)” ), not sure what I’d find.

What I found was a welcoming, passionate group of people who put in countless hours to support the Portland clubs. That first experience was so positive and inspiring, my son and I returned for the second tifo painting—this Cascadia rivalry masterpiece: “Scary Tales to Tell in the Park,” a 60-by-48-foot horror-inspired homage to some old-school Timbers history and the park the team has called home since 1975—and this time we had his best friend and that friend’s longtime TA member dad in tow. Two weeks before the match, we showed up at the warehouse to paint what the Tifo Committee calls “basically a large paint-by-number.” And it is. We were assigned a color, found that color already outlined and labeled on the canvas, and added our paint in the appropriate place. After our two-hour shift, we looked back and saw the tifo skull filled in. Job complete.

But our two hours pale in comparison to the labor that got the tifo to that point. Before there’s a tifo, there’s an idea. Tifo ideas come from the collective consciousness of the Timbers Army Tifo Committee and usually include time-relative commentary, pop-culture references, and/or just simply some kick-ass art. The Committee produces an array of tifos, depending on the season. The home opener, home Cascadia Cup matches, and home playoff matches all get one, as do matches designated to celebrate Pride and MLS’s show-racism-the-red-card initiative.

The Committee cultivates a creative community, and once the idea of a given tifo is settled on, it’s designed, projected onto the appropriate-sized canvas, outlined and labeled, painted, transported to the stadium where a group has already attached the riggings to the Providence Park rafters, raised in practice, stored, and then brought out for the match, to be raised again for the world to see at the end of the anthem.

When I think about Dairon Asprilla’s amazing bicycle in the 71st minute of that match, I can’t help but think about how special goals like that are an instant in happening but an absolutely involved process over the years that provides the moment for improvisation that could change a season.

This is what the tifo process is like: countless hours of labor, logistics, and passion. It’s love. It’s love for the community, the team, the game. It’s the same love that moves a player to propel in the air and strike the ball backward at a goal he can’t see.

Temporally, on video or in the memory, these legends never fade, yet in the physical world a goal like that happens in an instant, and a tifo is up for about 2-3 minutes. In both cases, the magic happens because the people involved put in the work.

And that’s what being part of this tifo process is—being involved, there’s a place in the game for everyone, and that’s what we’ve found in this group. There’s a place for you, you just have to show up. “I personally started painting tifo in 2013,” a member of the Tifo Committee told me. “I just showed up for a volunteer call….” They slowly made friends with others who did the same, and realized, “there’s a lot of different ways to get involved in the [107IST]; a lot of specific skills we look for that cover a wide variety of skill sets.”

I can stand with my back to goal and hurl myself in the air, but I have legitimate doubts about what happens next. I’m pretty sure it does not involve making contact with a crossed ball, in traffic, in a MLS derby, beating a very good ’keeper, and in a sense flipping a switch on a season. But I can participate in the moments that make the game. And that’s where we all come in. “The whole thing [with the tifo process] is trying to make sure everyone is feeling comfortable and welcome,” they told me, “and having a good time. This is supposed to be a fun time, supporting our club and our community.”

And players know it. When I asked Scot Thompson about his favorite memories playing in Portland, he pointed to being in the stadium that first time, when he saw Timber Jim high up on a snag, but he bookended that with nothing involving kicking a ball. “It was against Puerto Rico. It was like one of the last games I was playing,” he told me. Thompson was about to become the Timbers’ all-time leader in minutes played. “When the Timbers Army unveiled their tifo, it was ‘The Man with the Golden Heart.’” Thompson is referring to the July 23, 2009, TA tifo. “That was special—one of those moments that gave me chills. Even to this day, my kids can go on YouTube and watch it.”

“If you want to be Timbers Army, then you already are”—even if that means you were in the stands 26 years before the TA became official. It’s been different here, for everyone’s collective experience. “Well, my best memory, of course, is scoring that goal [against Seattle] and what was going on after that,” Tony Betts recalled of his Portland playing tenure. “And then the fans, of how quickly they got behind the team. And that's how you look at it, that the history of the families in Portland that have really stuck by the Timbers, through thick and thin.”

“One thing that really stuck out in my mind,” Willie Anderson told me of that 1975 season, “is we beat Seattle, and we had St. Louis in the semifinals in Portland.” (See “No Pity Land”.) “They put the tickets up for sale on like a Thursday or a Wednesday, because we were playing Saturday. We got into practice [at Civic Stadium] and Vic Crowe said, ‘OK, get into twos and follow me.’ And we ran out of the stadium, and there was a line right around the stadium, like five deep waiting to buy tickets. And we ran around the stadium, clapping the fans. It was amazing; I’ve never, ever done that before.” I wonder what Vic Crowe would have thought to see his name incorporated into that massive 2023 tifo.

When I think of and intellectualize all Willie Anderson accomplished in his career, there are so many Soccer Things one could point to and stand in somewhat awe of. But for Anderson, it was that moment at training nearly half a century ago that left an impression: “That was one of the best things I’ve ever done in my career, just jogging around the outside of these fans queueing up for tickets, and clapping them. Just a great feeling.”

The number one thing every player I talk to misses is the people. The teammates, the fans—being part of something bigger than themselves. Hands down, that’s what they all miss, and that’s where we all contribute.

At the end of the 2023 Timbers/Sounders match, the tifo needed to be taken back to the warehouse after the stadium started to clear of fans. It made for a second consecutive long night, but that didn’t matter. We made our way down to the field where the tifo was stashed for the game. About 16 of us carried the 2,880 square feet of used canvas from the field, up the stands, out onto Southwest Morrison Street and through the fans on the street, east to the warehouse. It was the lightest tifo I’ve ever touched. It could be the number of people helping, or the collective glow of a home team win, or maybe that’s just what happens when the moment is so much bigger than any one person.

In the first year Seattle competed in MLS, their head coach was new-to-the-rivalry Sigi Schmid. When the Sounders drew the then-USL side Timbers in the Open Cup, Schmid’s assistant coaches, Tom Dutra and Brian Schemtzer, stepped up. “[Brian and I] were like, ‘Look, Sig, this is going to be way bigger than our guys realize,” Dutra recalls saying. To his credit, Schmid stepped aside and let the longtime Seattle-area soccer legends handle some preparation. “[Schmid] had us speak to the team, about the importance of that game and what it means.”

Even with that battle-tested Cascadia experience, Dutra, like us, is a fan of the game above all. When I told him I took my son to help paint the tifo, he was pretty excited about what he’d see the next night, knowing how, through this competition, we’re all sharing the moment. The game. And that’s what it’s all about, no matter our role.

Schmid, Schmitzer, and Dutra were all still together with the Sounders when the Timbers entered MLS in 2011. At that point, on their third season, the Seattle side was happy to have the Cascadia company in the league. “Portland came up to Seattle,” Dutra recalls of their first proper MLS derby, a 36,000+ sellout, “and I remember Zig just looking at me and saying, ‘This is what football is all about in our country now.’ And I remember how much it meant to him to be the head coach of the Sounders, and then having Portland come up and be part of the league and MLS, and he was just so proud, you know; he was so proud to be part of that game. And Brian and I were so happy for him to be part of it.”

When a couple of midlife dudes walk into a warehouse with their 10-year-olds to paint a tifo, when a player walks into a locker room to help his new team, when any one of us comes in contact with the game, it’s all the same thing: participating—contributing a small and important verse to the ecosystem that was happening before us and will happen after us. To the things bigger than us, in the way we can. Showing up. Supporting the game. Supporting our club and community.

This is exactly where all of us belong.

The 2023 Timbers ended April where they started: in 9th place, just above the playoff line. A great road win avenging the early-season home loss to St. Louis City SC brought hope with the three points, as Yimmi Chará returned from injury to score the game winner. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

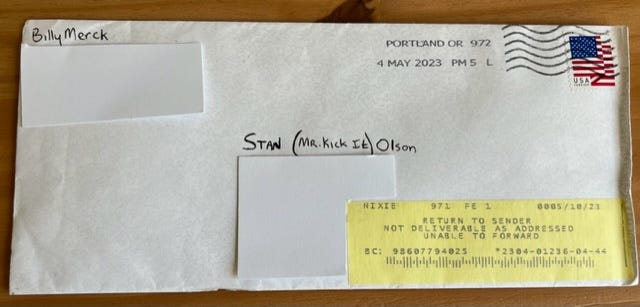

Similarly, my efforts to find Mr. Kick It! have mirrored the same cycle. I found a few phone numbers and an address. Nobody answered the phones, and the letter was returned, undeliverable.

But, like the Timbers this season, I’m not giving up. It’s only been three months, and I’m determined.

When you have a dream you try. Every time.